BY :

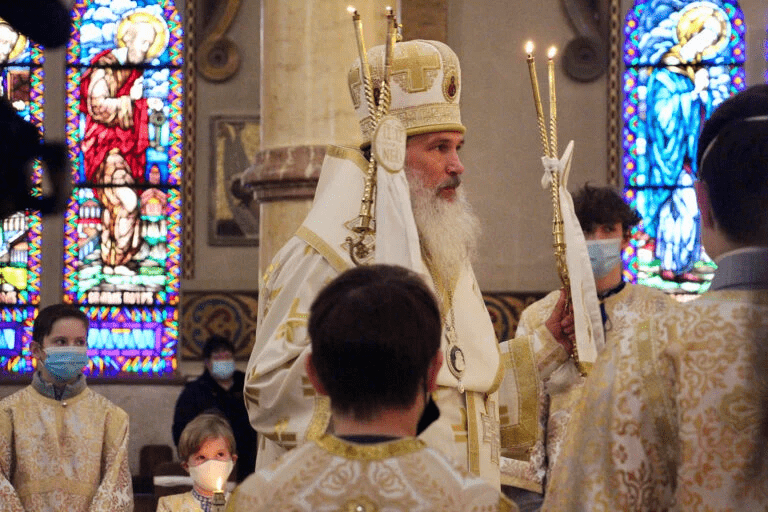

In cities with some of the largest Ukrainian populations in the United States, worshippers prayed for peace and an end to war Sunday (Feb. 27) as Russia threatened its western neighbor for the fourth straight day. Ukrainian Catholic Bishop Benedict Aleksiychuk leads a service at St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral, Sunday, Feb. 27, 2021, in Chicago. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

CHICAGO (RNS) — Everybody at St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral has family in Ukraine, said Tamara Nosa. It’s why she brought her family to the church in Chicago’s Ukrainian Village on Sunday morning, knowing how many people would turn out for the Divine Liturgy, including Roman Catholic Cardinal Blase Cupich and Ukrainian Catholic Bishop Benedict Aleksiychuk.

Nosa, 38, of suburban Plainfield, Illinois, said Sunday (Feb. 27) she is happy to see so many people protesting Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But, standing outside the cathedral surrounded by signs sporting the blue and yellow colors of the Ukrainian flag and emblazoned with messages of support for the country, Nosa still felt discouraged. Nothing is changing, she said.

The invasion continues. She checks in each day with her family outside the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv, where they’re hiding in their basement. They can hear sirens blaring outside.

What else is left to do but pray?

“I’m teaching my kids let’s go to church and pray. I think like God’s maybe going to help, I’m hoping, because nobody is helping right now,” she said. “I think we lost hope, you know? And it’s really, really bad.”

Tamara Nosa, far left, and her family outside St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral,

In cities with some of the largest Ukrainian populations in the United States, worshippers prayed for peace and an end to war Sunday as Russia threatened its western neighbor for the fourth straight day.

“Today we are all Ukrainians,” said Cupich, the archbishop of Chicago.

In Chicago — where more than 54,000 people in the metropolitan area identify as having Ukrainian ancestry, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates — several Catholic churches held special Masses and rosaries over the weekend to pray for peace in Ukraine and an end to the war. All rang their bells at noon Sunday in solidarity with the Ukrainian people — something they’ll repeat on Ash Wednesday, when Pope Francis has asked all believers and nonbelievers alike to fast and pray for peace.

Roman Catholic Cardinal Blase Cupich speaks at St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral, Sunday’s liturgy at St. Nicholas was sung by a choir of mothers and daughters — fitting, Cupich said, as “this moment is an opportunity for the whole world to reflect on what kind of world we want to leave to future generations.

“It is our moment in the history of the world to say, ‘Stop. No more. We want a different world for our children.’ That is what this moment is all about. That is why the entire world is raising its voice in outrage, but also support,” the cardinal said.

In New York City’s East Village neighborhood, Saint George Ukrainian Catholic Church welcomed Cardinal Timothy Dolan, Roman Catholic archbishop of New York, to join them in prayer.

New York City is home to the largest community of Ukrainian immigrants in the U.S., with around 130,000 in the five boroughs and tens of thousands more across the river in New Jersey. Many of them live in the East Village.

Bishop Paul Chomnycky, Ukrainian Catholic eparch of the Stamford diocese that envelops New York and much of New England, said one of the first phone calls he got after the invasion was from Dolan, offering support.

“It is exactly in times like this that true friends show themselves,” Chomnycky said.

Dolan previously had visited Saint George in 2014, during the Russian takeover of Crimea, he reminded the congregation, which included Roman and Ukrainian Catholics and even a state senator — Carolyn Maloney, the East Village’s representative in Albany.

“When you and I don’t know what else to do, we pray,” the cardinal said.

Near Pittsburgh, a banner outside St. Peter and St. Paul Ukrainian Orthodox Church also urged prayer for Ukraine.

Roughly 40 people gathered for worship Sunday in the colorful, incense-filled sanctuary in the Pittsburgh suburb of Carnegie, Pennsylvania. More than 20,000 people of Ukrainian ancestry call the Pittsburgh region their home, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates.

The Rev. John Charest, who has been at the 118-year-old parish for three years, gave a sermon on Matthew 25 — a gospel passage in which Jesus says those who served “the least of these” also served him.

“I am amazed by the grace of the Holy Spirit, all the workings he is doing right now,” Charest said, pointing to the outpouring of support for Ukraine.

But Charest didn’t sugarcoat the gravity of the invasion, which he says has been consuming almost all his time and energy. A third-generation Ukrainian, he and his wife are working to adopt three Ukrainian children who are currently living with a foster family in Kyiv.

“There was at least one night where they went next door and hid in the basement because the sirens were going off,” he said. “They haven’t seen any combat with their own eyes, they’re staying in the house. But they see the planes and they hear stuff. And they’re very nervous.”

Charest said he hadn’t anticipated Russia would launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. But as he wrestles with disbelief, denial and even righteous anger, he warns against anti-Russian sentiment.

“I want to be anti-war, and pro-peace,” Charest said. “That’s where I’m trying to guide my people. Please don’t hate anybody. That’s what got us into this mess.”

Victor Onufrey, who has been attending St. Peter and Saint Paul’s since the 1990s, is the son of Ukrainian immigrants. His wife is also from Ukraine and has family there.

“We pray, and we ask God to protect our country,” Onufrey said. “And I don’t pray for Russians to die, but I pray that these guys lay down their arms and just say, ‘no fighting.’”

A retired colonel from the Air National Guard, Onufrey thinks the invasion is motivated by Putin’s desire to rebuild the Russian empire.

“I don’t think religion is anywhere near a primary reason for this conflict,” he said. “I am hoping that with time, the common Orthodox faith of both sides will bring us together more than it drives us apart.”

In 2019, the ecumenical patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church recognized an independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The Russian Orthodox Church has refused to acknowledge the Ukrainian church’s independence and a branch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church remains loyal to Moscow.

St. Peter and St. Paul’s parish led a moleben, or prayer service, on Thursday and is preparing to serve an influx of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war. Members are also attending local rallies, and the church is partnering with a neighboring Ukrainian Catholic church to hold weekly prayer services until there is peace in Ukraine.

“We know God is love,” Charest said. “Yes, there are terrible things going on, but God is still there.”

Photo courtesy photo by Emily McFarlan Miller