(RNS) — For as long as he can remember, Eli Bonilla Jr. has felt like the unwilling recipient of a permanent visitor’s pass.

The son of a Mexican father and an Afro Latina mother from the Dominican Republic, Bonilla was often told he wasn’t quite Latino enough or Mexican enough or Black enough for whomever he tagged along with in the cafeteria or after school. As an adult, invitations to join certain groups seemed to often have more to do with scoring diversity points or pushing an agenda than with getting to know him personally.

While Bonilla is clear that the racial and ethnic components of our identities carry weight, as a Christian, he also believes reducing people to pre-packaged racial categories and stereotypes misses the breadth and depth of who each individual is in God’s eyes. And as a minister to young people with the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference and at a church in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, he cares about how an over-simplified approach to race could impact future generations, including his own kids.

“My wife is Palestinian American, and now we have two babies in the world,” said Bonilla. “The dedication I wrote says, ‘To my children, Ezekiel and Novalee, may your identity always be found in Christ alone.’”

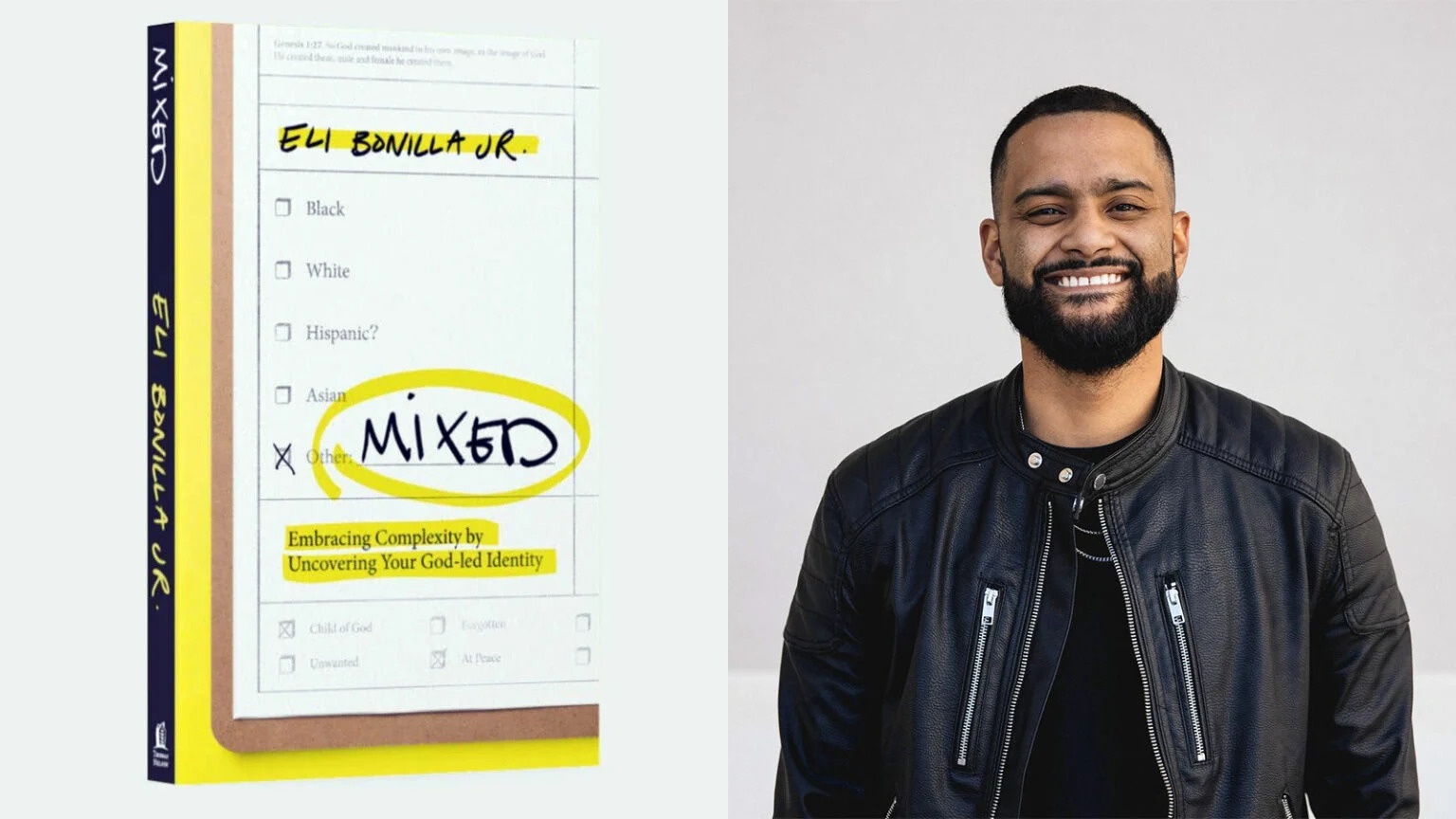

Religion News Service spoke to Bonilla about his new book, “Mixed: Embracing Complexity by Uncovering Your God-Led Identity.” This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell me the story behind how you came to write this book?

“

I like to say I was born into an identity crisis. When 2020 came and we were having conversations around Black Lives Matter, it begged the question, where do I fit in? As an Afro Latino, my cousins and I all share in a lot of the issues the Black community was talking about. Being stereotyped, followed around in Walmart, pulled over for no reason. I’ve been put on the hood of my car. I would start posting about things like that, but the pushback I would get online was not from the white community. It was from Mexicans, my friends, people within my community who were ‘All Lives Matter’ people.

The Mexican community also said it’s awesome that you’re being loud about this, but it’s also a bit hypocritical that you’ve been quiet about the fact that we have thousands upon thousands of Mexican and Central American children in cages on the border. Where’s the uproar? And I’m like, well, you’re right. So hold on, let me broaden my definition of justice. And the moment I posted a little more broadly, I would have people from the Black community tell me, ‘hey, whoa. Right now it’s not the time. You’re diluting the conversation. So put a pause on the cages and put a pause on the Latino thing.’ It really put me in a confusing ethical moral situation because I am both of those things. I’m Black, but I’m also Mexican. Eventually it led to a talk that I did and then an opportunity to write a book.

Can you talk about how the questions “What are you?” and “Where are you from?” miss the mark, especially from a biblical standpoint?

In one of the chapters I talk about the difference between identifiers and identity, identifiers being the way I look, my skin tone, the way I dress, the way I hold myself, things people can see physically. But identity is something so much deeper. I think my big issue with the conversation is we’re trying to solve soul-deep complexity with skin-deep conversations. Science and society can tell you what you are, but only God can tell you who you are.

When I got caught up in the “what,” I often became a caricature of myself. If it’s a smoother social interaction for me to play a version of what you think I should be as a Mexican, as a Dominican, as a second-generation Latino immigrant, then I’ll be a caricature, and you’ll never get to know who I am. If I believe God is the ultimate designer, the best place I can go to find out who I am, not just what I am, is to go back to a relationship with the one who created me.

What are some ways Christians can honor the complexity of other people’s stories without pretending race and ethnicity don’t matter?

Revelation 7, verse 9 talks about what happens when eternity is in place. It says that before the throne of God are people from every nation, every tribe and every tongue. Obviously, God has an eternal importance to those distinctions that we cannot ignore. And so for me to ignore ethnicity, the places people come from, their language, is for me to ignore what God deemed eternally important.

Now, in John 17, Jesus says, ‘Father, may they be one as you and I are one so that the world will know that you sent me.’ God’s goal for humanity and his church is not diversity, it’s unity. We put the cart before the horse when we say we need to diversify, we need to make sure people look different. People are already different. The whole challenge is, how can we unite?

Whenever people suggest we just be colorblind, the problem is, if we took all our distinctions away, then we would have uniformity and not unity. Christ called us to unity, which means you keep your distinctions, but you are united together. And that shows a greater love.

What do you mean when you say Jesus is mixed? And what we can learn from Christ’s mixed identity?

Jesus is born into complexity. His family is woken up in the middle of the night, and they have to flee to Egypt, the place that has a history of 400 years of enslaving the Jewish people. And then he was raised in Galilee, in Nazareth, which has a bad reputation. He comes from a border town, with a lot of Roman and Greek culture coming in and out. They were far away from Jerusalem. It is important to look at the life of Christ in all he navigated — coming from a father that was a carpenter, going about his heavenly father’s business, but still honoring to his earthly mother — all of that complexity speaks to the fact that he can handle the complexity within us.

Jesus didn’t come from a good lineage. Luke writes about the fact that he had three Gentile women in there and one of them was a promiscuous woman. He was from a mixed background, of mixed lineage, with mixed company, in a mixed geopolitical era, with mixed reviews. He’s seen with prostitutes and tax collectors. Yet he was able to leave a blueprint to say, I am the one that broke all the boxes. Whenever you feel boxed-in, you can follow me and trust that regardless of the complexity you come from, I can give you clarity to where you’re going.

In the section about Paul, you write about how God calls us to a life where nothing we’ve been through is wasted. Do you think there are any exceptions to that idea?

There’s the story of Joseph in the Bible, who says, ‘what you have intended for evil for me, God has intended for good.’ He didn’t forget the evil he experienced. For people that are survivors of tragedy, the Bible is not a call to forget or diminish what someone has gone through. But there is something triumphant and transcendent that comes with Christ coming in and not dismissing where you’ve come from, but redeeming your soul.

Paul talks about how he’s been redeemed after co-signing murders, and later gets stoned, whipped, beaten, starved. What I believe is comforting for everyone, regardless of background, is that redemption begins with bringing all your trauma and all the tragedy of your life to Christ. Christ is in the business of redeeming broken people. But Christ was broken, too, so that he would make a path back to wholeness. He went through the most horrific death so he could conquer it.

Who do you hope reads this book and what do you hope they take away from it?

I hope everyone buys this book. But the obvious answer is people that either are mixed racially or ethnically because, in many ways, we’re born being asked to choose between Black or white, even on the forms you fill out at the doctor’s office.

I would put into a similar category people in mixed families. How can we gain some unity together with the distinctions in our household? I think this book is also for people that are looking to have a different perspective on the race and ethnicity conversation. And then lastly, anyone that is struggling with knowing who they are. I don’t think that the answer for justice, equality and unity is the diminishing of anyone. And so if there’s anyone that feels incomplete, unsatisfied, lost, it might stem from diminishing themselves. Anyone struggling with that, this is a book for you.