LOS ANGELES (RNS) — When Brian Chung worked as a campus minister at the University of Southern California several years ago, he noticed that many students weren’t interested in the Bible.

Especially for those who had never read it before, the scripture could be intimidating and dense — and at more than 1,000 pages long, they often didn’t know where to start.

“We would give out Bibles to people who were interested, and I remember seeing someone who didn’t grow up Christian open the Bible, flip through the first couple pages and sort of give up,” said Chung, 30. “They put the Bible back into their backpack.”

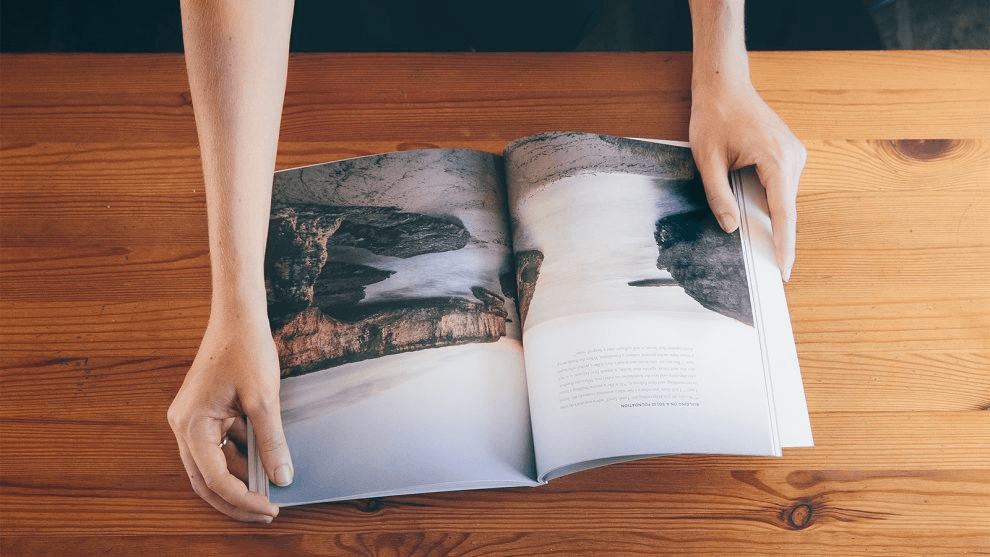

This inspired Chung and his friend Bryan Chung, both artists (and unrelated, despite their nearly identical names), to re-design portions of the Holy Book with original photography and a sleek layout to better appeal to a millennial aesthetic.

Their company, Alabaster — which started as a 2016 Kickstarter campaign that raised more than $60,000 and formally launched in 2018 — now sells seven books of the Bible, created to look like specialty indie magazines such as Kinfolk, Drift and Cereal.

The company has sold 16,000 copies of the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Romans, Psalms and Proverbs so far and is aiming to produce a version of Genesis later this year.

“We really take in visual media more than any other type of media,” Bryan Chung, 24, said of millennials and Generation Z. “We respond to websites and books based on how they’re designed. Our culture is becoming increasingly visual. We wanted, instead of shying away from that, to think about how we could do that in a faith-based space.”

While Alabaster’s products may be innovative, the concept is nothing new, said Jeffrey Siker, professor of New Testament at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Scrolling through the Bible section on Amazon, he said, proves the point. There’s the “Jesus Storybook Bible,” “My Creative Bible,” “Adventure Bible for Early Readers,” “Celebrate Recovery Study Bible,” “Boys Bible,” “Bible for Teen Girls,” “Beautiful Word Coloring Bible,” “Every Man’s Bible,” “Life Application Study Bible” and the “Woman’s Study Bible.”

“It’s still the single bestselling book every year, bar none,” Siker said of the Bible. “It’s still being produced endlessly. So the question is, what form should it take?”

Melinda Bouma, publisher of Zondervan, one of the largest Bible publishers in the world, said the company’s first niche Bible was the “New International Version Student Bible,” which came out in 1985. Since then, Zondervan has created dozens of niche Bibles for all demographics, which now make up half of the company’s sales, she said.

Zondervan’s latest is its artisan collection Bible, released this month. After noticing a trend of hand-painted Bible covers on the e-commerce platform Etsy, Bouma said the company hired an artist to paint original Bible covers that were then mass printed on linen to emulate a custom painting. This collection also features foil stamping, verse art and an original font — all of which Bouma said appeals to a millennial aesthetic.

Bibles like Alabaster’s may be a response not to the proliferation of print Bibles but to competition from online scripture resources. “Millennials grew up as digital natives,” Bouma said. “We’ve had unparalleled access to the Bible at our fingertips for most of our lives. You can go online at any point and read the text if you like. That only means that the aesthetic and the quality and the craftsmanship of the Bible matters more than ever. If I think of a barrier to reading the Bible today, it’s ‘Why should I buy a Bible when I can find it online?’”

Brian Chung said Alabaster offers a contrast to digital Bibles by encouraging readers to take their time with the scripture and to reflect on the meaning of the photographs.

“It’s another option that allows people to engage with the images around the text in a slower, more experiential way instead of just scrolling on your phone,” he said, noting that Alabaster’s Bibles were designed with everyday personal scripture reading in mind.

Bryan Chung said the images, like the illuminated Bibles of the Middle Ages, aid this.

“When you look at Christian culture, most of the ways that we experience God are through the written word or spoken words — when you listen to sermons, which is spoken, or when you read, when we sing songs,” he said. “For us, there’s this whole visual language or visual medium that I think we can also experience God through.”

By selling only selected books of Scripture — and not the entire Bible itself — Alabaster shares at least one thing in common with digital Bibles, said Siker.

“When you only have one book, you end up having a fragmented picture of the Bible,” he said. “This is what has happened recently with digital Bibles — they’ve become unbound. So people read and they have no idea that the Gospel of Mark is bumping up against the Gospel of Matthew. They don’t have a tangible feel for the text as a whole.”

In addition, he said, Alabaster Bibles’ clean designs mean readers are missing the footnotes, maps and references that most traditional Bibles have as a way to help the reader better understand the text.

“It’s kind of a non-contextual Bible,” said Siker.

Brian Chung said Alabaster — which takes its name from a biblical story in which Jesus references beauty — serves a different role. Designing portions of the Bible with art at the center, he said, makes the scripture more approachable and easier to talk about.

“With our product, we see people really take it in,” he said. “They slowly process it, they look through it, not just the story or the words, but the imagery. It’s really cool seeing how a simple design change can impact how people engage with the Bible.”