BY : Religion News Service

(RNS) — For the entirety of his adolescence and young adulthood, YouTuber Rhett McLaughlin strived to live as the epitome of a winsome Christian. He was raised in a devout home in North Carolina and previously worked as a full-time missionary on college campuses in the South.

But, by his early 30s, his relationship with God was torturing him. Or, as he put it, “I constantly, constantly thought: Oh, crap, what if I’m wrong?”

During that time — about a decade ago — McLaughlin, alongside his lifelong friend and business partner Link Neal, was churning out hundreds of episodes of a YouTube series, “Good Mythical Morning,” chronicling the duo’s most memorable high school pranks and debating over the best superhero. Amid producing the nonexplicit, lighthearted and distinctly internet-y content for a growing audience, McLaughlin was reconciling a decadelong faith deconstruction.

At that point, he also had kids of his own whom he was raising in church, yet he was “always a skeptic.” And, as he studied books on evolution and the age of the Earth, he came to a place of outwardly rejecting his past identity as an evangelical Christian.

Today, after the “unraveling” of his religion, McLaughlin, 44, identifies as a “hopeful agnostic.” He recounted that spiritual journey in his debut album, “Human Overboard.” McLaughlin chose the pseudonym “James and the Shame” after his middle name to separate the new music venture from his happy-go-lucky YouTube videos.

In an interview with Religion News Service, McLaughlin, who appeared far more serious than his 17.7 million subscribers may be used to, explained that nothing is too personal for his therapy-turned-country music project.

The record isn’t McLaughlin’s first time expounding on his ups and downs with America’s brand of evangelicalism. Via their longform podcast, “Ear Biscuits,” McLaughlin and Neal discussed their winding walks away from the church, including topics such as their “lost years” as missionaries and having sex for the first time on their wedding nights after years of purity culture conditioning.

The positive response McLaughlin received for the channel’s series on deconstruction in 2020 prompted him to spend his pandemic free time writing lyrics as a healing exercise. Since this introspection helped him, McLaughlin, with the blessing of his therapist, figured releasing the songs could help listeners too.

The album, coming out Sept. 23, is a total abandonment of the traditional, evangelical perspective. Some songs are written for his wife, another is about him and his parents reconciling their spiritual differences. His first single, “Believe Me,” dropped on July 15 and was written directly to God. The lyrics, a heartbroken but stoic Americana anthem, are complemented by steel-stringed instruments.

The reviews of the song have been overwhelming, though not entirely encouraging, according to McLaughlin’s Instagram post from July 20. Some listeners accused McLaughlin of not understanding the grace of the gospel, saying he was never really a Christian, since many Christian theologians argue one cannot lose one’s salvation. A few commenters said his de-conversion occurred because he moved to Los Angeles. None of those interpretations is correct, McLaughlin said.

Some listeners have even gone after his family, saying a “true relationship with Christ was never modeled” for him. James, his stage name, also happens to be McLaughlin’s father’s name, and his grandfather’s name. Still, McLaughlin wants to set the record straight: He harbors no religious trauma from his upbringing.

“I’ve had folks tell me that I deconstructed from something that wasn’t even a true expression of Christianity,” said McLaughlin. “Don’t write me off as a theological footnote.”

His father also gave McLaughlin a proclivity for the country sound. Born in Macon, Georgia, and raised in North Carolina, as a child he listened to a curated soundtrack of folk legends such as Merle Haggard and George Jones. McLaughlin felt country music was an appropriate vehicle for his message. And, he said, he stuck with the genre despite the perfect paradox of conveying progressive lyrics with a twang.

“It’s ironic to sing about these sorts of messages in a genre that is considered the most conservative form of music in the United States,” said McLaughlin.

The “Shame” portion of his stage name stems from nagging residual emotions, namely regret. As an example, he recounts when his roommate in college at North Carolina State University came out as gay in the local newspaper. His roommate said he feared losing his residence since McLaughlin owned the apartment. McLaughlin said he gave a trite love the sinner, hate the sin response to his roommate at the time, though he did not kick him out.

“At this point, I obviously regret whatever I said to him,” said McLaughlin.

McLaughlin and Neal are far from alone in deconstructing. For decades now, each new generation has reported less religiosity than the one before it, according to Pew Research. As pews empty, many who’ve deconstructed flock to digital spaces with fellow dissenters of organized religion. Glancing at the comment section on “Believe Me” yields an influx of support for McLaughlin’s lyricism and a resonance with his experiences.

Music has always been a mechanism through which McLaughlin understands the metaphysical. In a journal entry from his late 20s, which he shared via podcast, he wrote, “the significance of my faith is not found in a well-reasoned argument. Rather, it rings true like a musical note when it hits my resonant frequency.”

These days, McLaughlin has changed his terms but not his tune, saying the “fabric of the universe having intention still rings true in my ear.”

As of Aug. 4, McLaughlin’s only live performance for ”James and the Shame” is scheduled for late October during Mythicon, a conference to celebrate his and Neal’s media company at the Star Hill Ranch outside of Austin, Texas.

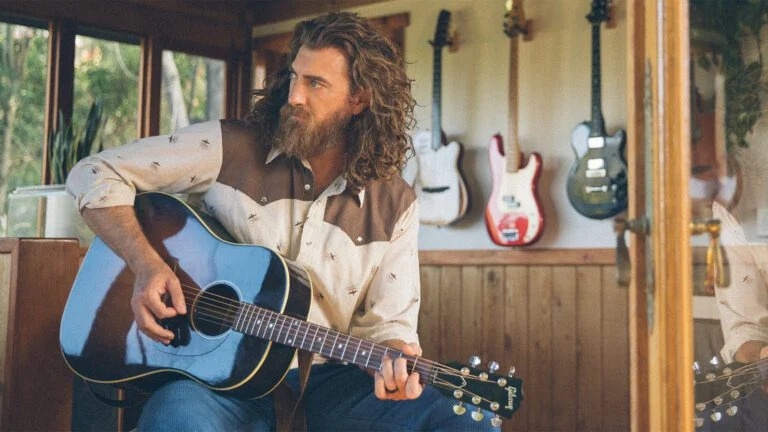

Rhett McLaughlin. Photo by Anna Webber