(RNS) — For younger Americans and even many baby boomers, psychoanalysis — true, Freudian-inspired analysis, not therapy — exists as a kind of historical artifact, glimpsed in Woody Allen movies or old New Yorker cartoons.

Yet we are ever more aware of people whose mental suffering requires more than weekly therapy, but doesn’t rise to the level of hospitalization or inpatient care — the gap that psychoanalysis is often deployed to answer.

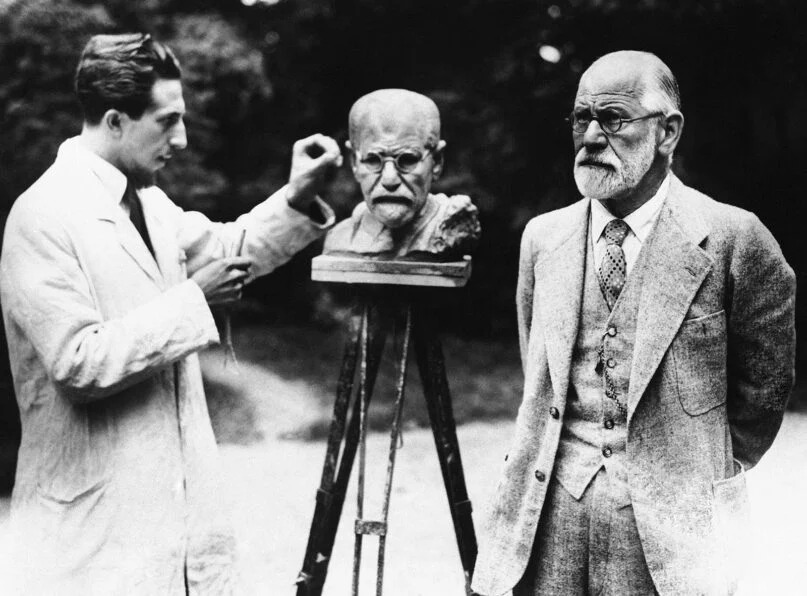

It’s little wonder, then, that psychoanalysis’ most famous exponent, Sigmund Freud, is experiencing a resurgence.

A recent New York Times op-ed by Joe Bernstein amasses the evidence for our Freudian moment: a proliferation of memes and social media accounts, more clinicians from more diverse backgrounds embarking on psychoanalytic training, younger patients entering analysis, a new film in development starring Anthony Hopkins as Freud and, tellingly, more cultural openness about sexual expressions and curiosities that seem, all of a sudden, no longer taboo.

Religious people and institutions, long thought to be culturally distant from psychoanalysis in its historical, medicalized form, would be wise to engage this reconsideration of Freud’s clinical and cultural legacy.

For decades, the “Freud wars” comprising debates about feminism and sexuality, the validity of recovered memories and the psychoanalytic practitioner’s relationships with patients have contributed to a growing consensus that, some central insights notwithstanding, Freud was something of a charlatan.

Add to this that, even as mental health awareness is at an all-time high and stigma for seeking treatment has declined, insurers and the health care system prefer quicker, cheaper methods of treatment. Psychoanalysis, by contrast, is inefficient, expensive and time-consuming. It usually involves multiple sessions per week and can go on for years, focusing more on free association, dreams, fantasies and the unconscious mind than on divining and ameliorating symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Of course, it’s possible for weekly check-in therapy to take a more deep, analytic style and for long-term psychoanalysis to involve medication management and day-to-day functionality issues. But in general, analysis remains more traditionally in the mold of Freud.

Conservative Christians have often been among the most resistant to mental health treatment in general, and instead point troubled souls to Christian (or “biblical”) counselors, fearful that mainstream clinicians might lead them astray. Psychoanalysis, generally unavailable outside urban areas and typically associated with people with the highest levels of educational attainment, is an activity indulged by those whom Christians on the right tend to refer to sneeringly as “elites.”

Historically, too, familiar biblical concepts of sin, forgiveness, grace and redemption are largely absent from the lexicon of psychiatry and clinical psychology.

Perhaps a deeper religious engagement with psychoanalysis could yield a more comprehensive view of the mind and soul — and what mental frameworks lead to healing and human flourishing. In addition, religion’s emphasis on rightly ordered desires and psychoanalysis’s intensive probing of desires themselves may be more complementary than is often assumed.

Among Freud’s more thoughtful, if controversial, interpreters was the late Philip Rieff, a conservative sociologist who argued that the language and ethos of “the therapeutic” had subsumed elite culture and, eventually, the broader culture as well. The popular podcast “Know Your Enemy” has discussed Rieff and Freud in recent episodes.

Rieff was sympathetic to Freud and, contrary to many who associate Freud with allowing or even demanding deference to liberatory and libidinal impulses, he saw Freud as allied with the repression on which civilized society depends. Rieff also saw religion as central to the project of maintaining civilization. Rieff, who was a secular Jew, strongly influenced Christian conservatives such as Carl Trueman and Rod Dreher.

Speaking about Rieff, commentator Park MacDougald suggested we heed his view that the human mind is attuned to “the demands of the sacred, which also happen to be the one thing that our culture seems genuinely comfortable repressing.”

Freud will always have his detractors on the left and the right. But the distance between psychoanalysis and faith is needlessly wide. In this moment of reconsideration, religious leaders and psychoanalytic practitioners should take a step toward each other.

The two need not be enemies. Conceptions of sin, forgiveness, grace and redemption can be recognized alongside deep analytic work on family systems, dreams and the unconscious. Healing deep mental or emotional wounds naturally makes people morally better. Freud’s insights about parental influences and the unconscious mind may lead to deeper commitments among people who love God as father and church as mother.

And believers can be comforted that their conviction that repressing certain impulses can be beneficial is widely shared outside of religious circles; it has been, and will remain, a live debate.

Clinicians, too, might learn a lot if they spent some time in pews, or at least talking to more people who do. For either side, there is nothing to fear.