BY : Martyn Whittock Christian Today

The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews reminds Christians that they are surrounded by a great “cloud of witnesses.” (NRSV) That “cloud” has continued to grow in size since then. In this monthly column we will be thinking about some of the people and events, over the past 2000 years, that have helped make up this “cloud.” People and events that have helped build the community of the Christian church as it exists today.

Christianity in modern China

In August 2023, the US-based Pew Research Centre published data provided by responses to the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) question: “What is your religious belief?” This revealed that, in 2018, about 2% of Chinese adults (c.20 million people) self-identified as Christians. Of these, Protestants accounted for about 90% (c.18 million adults), while the remainder were mostly Roman Catholics. Other surveys, using slightly different question wording, report similar stats. In the 2018 World Values Survey (WVS), 2% of Chinese adults said they believed in Christianity; in the 2016 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), 3% said this.

In contrast, some media reports and academic papers have suggested that the number of Chinese Christians may be much larger than these surveys suggest. These have included estimates as high as 7% (100 million) or even 9% (130 million) of the total Chinese population, including children. However, it should be noted that, to date, no national surveys measuring formal Christian affiliation come close to these much larger figures.

Nevertheless, the picture may be more complex still. This is shown in the fact that the cumulative share of Chinese adults who say they “believe in” Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu (the term Chinese Catholics use for God and literally meaning ‘Heavenly Lord’ or ‘Lord of Heaven) is 7% (c.81 million adults), according to the 2018 CFPS survey. It should be noted that such larger figures include those who also believe in one or more non-Christian deities, such as Buddha, ‘immortals’ (Taoist deities), or have Islamic beliefs. In contrast, in this research, the number of Chinese adults who say they believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu- and do not believe in other deities – is about 3%. This is closer to the CGSS stats we started with.

All of this reveals how difficult it can be to get an accurate estimate of the number of Christians living in modern China. The matter is made particularly complex because only those churches authorized by the communist government are officially allowed to operate. In reality, many Chinese Christians are members of “underground churches” (dixia jiaohui) or “house churches” (jiating jiaohui). These Christians face restrictions on Christian activities outside of registered venues, the policing of online activities, police raids on ‘unregistered’ gatherings, difficulties at work and official suspicion of faiths which do not conform to President Xi Jinping’s call for the “Sinicization of religions.” As a result, large numbers will not appear on any published statistics.

Many of these Christians communities trace their origins – either directly or by influence – to the work of European and US missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries. This ‘foreign’ connection lies behind the official view that they fail the test of the campaign for the “Sinicization of religions.”

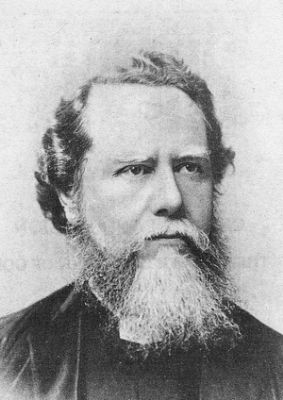

Of the many who worked as missionaries in China in the 19th century, one whose work had a particularly enduring character was James Hudson Taylor, founder of the China Inland Mission (CIM), which was responsible for taking over 800 missionaries to China. In time the CIM grew into one of the largest Christian missionary movements on earth. It became the Overseas Missionary Fellowship in 1964, and today operates as OMF International.

The start of Taylor’s faith journey

James Hudson Taylor was born in May 1832, the son of James Taylor – a pharmacist and lay preacher – and his wife, Amelia. They lived in Barnsley (Yorkshire). Taylor seems to have lost his faith for a time during his youth, but by 1849 – just one month after his sister resolved to pray for him daily – he had a change of heart through reading a Christian tract.

He wrote of how his belief was now that: “The promises [of God] were very real, and prayer was a sober matter-of-fact transacting business with God, whether on one’s own behalf or on behalf of those for whom one sought his blessing.” It was a radical transformation.

Soon after, he resolved that he would travel to China as a missionary. He prepared himself for this new calling by reading books on China; studying the Chinese Gospel of Luke; and also studying medicine in London in 1852. He had not completed these studies before he travelled to China for his first visit. It was the start of an extraordinary relationship with a nation, its people and its culture.

Missionary work in China

Taylor sailed from Britain in September 1853 and disembarked in Shanghai in March 1854. He arrived in a land wracked by the civil war of the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64). It has been estimated that somewhere between twenty and thirty million people died due to this rebellion and related upheavals. Some figures have ranged as high as fifty million deaths. The suffering in China was enormous.

Taylor saw that many Christian missionaries had adopted fairly comfortable lifestyles, and that few went inland to the poorer rural areas of China. Despite the turmoil and danger, Taylor resolved on a different approach to missionary work. He adopted Chinese dress and wore his hair in the manner of the contemporary Chinese. His aim was to overcome social barriers and to make the Christian message more accessible and less ‘foreign.’ In this he followed the example of the German Lutheran missionary Charles Gutzlaff (died 1851 in British Hong Kong) whom Taylor called the “grandfather of the China Inland Mission,” due to his pioneering missionary work, including wearing local dress. The Chinese Evangelization Society, which he formed, was the one which sent Taylor to China. Until 1860 Taylor worked under the authority of the Chinese Evangelization Society in southeast China.

It should be noted that Gutzlaff was a complex and controversial character. Closely connected to European imperialism, he defended the use of force in China by these outside powers; he was accused of gathering intelligence for the British government; critics felt he rushed to baptize converts, who soon fell away from faith; and he was defrauded by (apparent) converts he employed to spread the faith but who inflated numbers of converts and sold the gospel books he sent out with them.

While Gutzlaff was – his critics asserted – too distant from what was actually happening on the ground in China, Taylor travelled extensively, preaching, and also bringing in medical supplies.

Determined to live among the local population he moved to a little house from where he could meet and befriend local Chinese. Moving out of the foreigners’ compound brought risks. A cannon ball hit the house and caused him to move back into the foreigners’ compound before his house was burned down. He mother kept the cannon ball as a symbol of the protection she believed that God had provided for him.

Despite these risks, Taylor and his co-workers continued preaching and distributing Christian literature and he was determined to be active at the grass-roots level of the missionary work. Over time he mastered several Chinese dialects that he used in his preaching.

In 1858, in Ningbo, Taylor married Maria Dyer, who was his companion in the work until her death in 1870. Although ill health forced Taylor to return to England in 1860, he continued to be very concerned for the Chinese populations who lived in the provinces to which missionaries rarely, if ever, travelled. In 1865 he wrote China’s Spiritual Need and Claims and founded the China Inland Mission (CIM). Its goal – as the name indicates – was to work in China far from the port cities. By 1866 the CIM had recruited twenty-two missionaries, including the Taylors. The first party of sixteen, including Hudson and Maria, sailed for China in 1866. The Taylors were accompanied by their four children. Eighteen more missionaries followed in 1870. Soon the mission grew in both numbers and geographical reach. By the end of 1887, 102 new missionaries travelled to China as part of the CIM’s activities. In 1888, the first North American party was sent out to China.

In China, Taylor pursued a policy whereby church buildings were built according to Chinese (not foreign) design, and in which the leadership was made up of Chinese Christians.

The work was tough. The Talor’s lost a daughter to meningitis in 1867, a baby son to malnutrition in 1870, and Maria died from cholera only a few days later.

After returning again to England, Taylor married a fellow missionary Jane Elizabeth Faulding, and they returned to China in 1872. Taylor spent the rest of his life combining active work in China, with administrative duties and travelling to other countries to publicise the work in China and recruit more missionaries. While out of China he kept close contact with those working there as part of the CIM.

Taylor played a prominent part at the General Conference of the Protestant Missionaries of China, which was convened in Shanghai in 1877 and 1890, and which sought to coordinate activities. He retired from the administration of CIM in 1901. After the death of his second wife in Switzerland, in 1904, Taylor returned to China for the final time and died in Changsha, Hunan, in 1905. He was buried beside his first wife, Maria, in Zhenjiang, in Jiangsu Province, China. The small cemetery, near the Yangtze River, was built over with industrial buildings in the 1960s, during the rapid industrialisation of modern China. In 2013 the land was redeveloped, the industrial buildings were demolished, and it was found that the Taylors’ tombs were still there. The graves were excavated with the surrounding soil and then moved to a local church. The original grave marker included these words:

“A MAN IN CHRIST” 2 Cor. XII:2

This monument is erected

by the missionaries of the China Inland Mission,

as a mark of their heartfelt esteem and love.

The significance of Taylor and the China Inland Mission

By the time of Taylor’s death, in 1905, the China Inland Mission was an international body in which 825 missionaries worked, in all eighteen provinces of China. There were over 300 mission stations employing over 500 local Chinese helpers, and it had 25,000 Christian converts.

A number of key characteristics stand out from Taylor’s approach to missionary work. These are: total financial dependence on God, with no guaranteed salary; close identification with the Chinese people; working in all the provinces of China; the mission administration being based in China; a nondenominational evangelical character to the work.

The China Inland Mission, known for a time as the Overseas Missionary Fellowship and now OMF International, carries on the missionary work started by James Hudson Taylor. Today it is an international interdenominational evangelical Christian missionary society, “with a heart for East Asia,” with its international centre in Singapore.

Martyn Whittock is a historian and a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England. The author, or co-author, of fifty-six books, his work covers a wide range of historical and theological themes. In addition, as a commentator and columnist, he has written for several print and online news platforms and is frequently interviewed on TV and radio news and discussion programmes exploring the interaction of faith and politics. His recent books include: Trump and the Puritans (2020), Daughters of Eve (2021), Jesus The Unauthorized Biography (2021), The End Times, Again? (2021), The Story of the Cross (2021), Apocalyptic Politics (2022), and American Vikings: How the Norse Sailed into the Lands and Imaginations of America (2023). He is currently writing Vikings in the East: From Vladimir the Great to Vladimir Putin, the Origin of a Contested Legacy in Russia and Ukraine (2025 forthcoming).

Photo Courtesy :