(RNS) — When he first saw clips of videos showing a controversial encounter involving white Catholic students, a Native American man and a group of black men yelling racist and homophobic slurs at the students, Bruce Haynes was intrigued.

“I heard the mess,” said Haynes, professor of sociology at the University of California, Davis and author of the new book “The Soul of Judaism: Jews of African Descent in America.”

Then he thought, “Look at the Black Hebrews there.”

But therein lies the problem, he said.

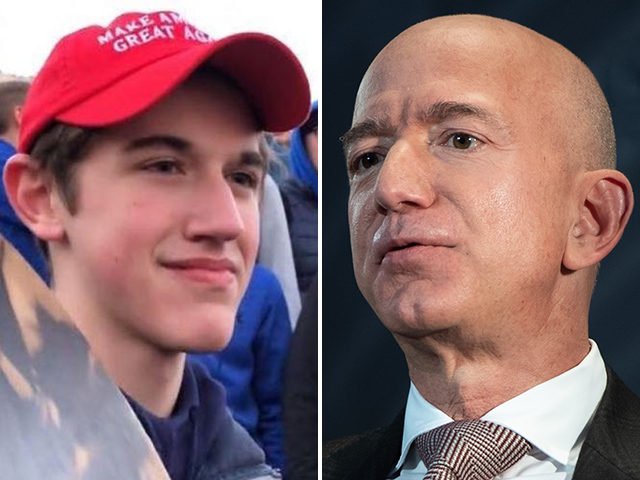

Many different groups and congregations around the country have taken on the term “Hebrew” or “Israelite.” This group in Washington hurling insults Friday (Jan. 18) at the Catholic students, who had attended the March for Life that day and many of whom were wearing Make America Great Again caps, in no way represents the many other groups, according to Haynes.

“The challenge is no one has really done a systematic study of all the different persuasions of people who self-identify,” he said.

While some black groups that identify as “Hebrew” or “Israelite,” such as a nearly 100-year-old Ethiopian Hebrew congregation in New York, are more mainstream, others have been labeled as hateful by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Some groups, Haynes said, send congregants to yeshivas, speak Hebrew and recognize the Talmud, while others are more aligned with Christianity. The latter may also refer to themselves as “Hebrews.”

This Wild West of Hebrew Israelite identification concerns Rabbi Capers Funnye of Beth Shalom B’nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation in Chicago.

“I wish that the news outlets would have identified the individuals or the group as the Israelite School of Universal Practical Knowledge,” he said. “We have never — in the history of our community — assaulted, defamed or spoken in a derogatory manner to any person or persons ever. We respect every person. It does not matter. Whatever their ethnicity, we are totally respectful to them.”

An ISUPK leader, who goes by the name General Yahanna, denied that his group was involved in the incident, but he said he understands what motivated the individuals confronting the students.

Haynes, an African-American who grew up middle class in Manhattan, attended a predominantly Jewish prep school and has participated in Jewish communities since he married his Jewish wife 22 years ago, said he also draws a distinction between the street preachers in the videos and other black groups with stronger Jewish ties.

He has spent two decades interviewing and studying Jews of African descent, whom he met in synagogues.

“I look at my research and the fascinating individuals that I met, and I listen to some of the things that are being said on television,” he said of the video. “These are not the same people. Rabbi Funnye would never be caught dead saying the things that those guys were saying.”

An “extremist fringe” of the Hebrew Israelite movement — itself a black nationalist theology whose origins are in the 19th century — holds that African-Americans, and not the people many think of today as Jews, are God’s chosen people, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The extremist groups believe that the former, and not the latter, are the true heirs to the Hebrews of the Old Testament.

The problem began in this instance with the news coverage, Funnye believes.

“Although most Hebrew Israelites are neither explicitly racist nor anti-Semitic and do not advocate violence, there is a rising extremist sector within the Hebrew Israelite movement whose adherents believe that Jews are devilish impostors and who openly condemn whites as evil personified, deserving only death or slavery,” the center states.

Of late, the rhetoric of the extremist groups has been “steadily heating up,” the center adds.

Funnye says that groups such as the ISUPK, who he says practice aggressive and verbally abusive street preaching, tend to operate in places like Philadelphia and New York, but not Chicago. That leads to less confusion in his neck of the woods.

But he still objects to them using the term “Hebrew Israelites.”

“I can assure you that we have nothing to do with this group whatsoever, in any way, shape, form or fashion,” he said.

If the group in the videos was identified by name, he said, “that would go a long way in helping to defuse and keep us from being lumped together with groups like this.”

Yahanna, the director of the Israelite School of Universal Practical Knowledge, said he understands the motivation of the men in the video.

He said they are not part of ISUPK; if they were, he would have trained them, as he does all of the group’s members, to speak differently.

Still, he said, the ISUPK expects to be demonized in the media, which it sees as part of a broader history of degrading black men for speaking out about oppression in America.

“Of course, we are looked at as instigators and troublemakers, but the entire Republican Party is not looked at as troublemakers for being racist,” he said.

Wearing pro-Trump apparel, he argues, is also a statement about race.

“In today’s black society, any white man wearing a ‘Make America Great Again’ hat is, in essence, wearing a white Ku Klux Klan hood and is looked at and viewed that way by black people,” Yahanna said.

The ISUPK, which “vehemently” presses that it isn’t affiliated with any other group or organization, sees itself as tied to Harlem-based Hebrew Israelites going back to the 1900s, according to Yahanna.

“We would love to be identified separately from anybody else, because of course, we don’t want to be blamed for any of the actions of someone else,” Yahanna said. “However, black people have been lumped together and propagandized for as long as we can remember, from the days of slavery. We’re almost used to being lumped together.”

He added, “We’d love it to be another way, but what can you do?”

Yahanna also questioned the effectiveness of groups that use tamer language to get their message across.

“We’ve learned over the years that talking nicely to our own people is ineffective,” he said. “Our people have had a very, very hard time in this country, and it takes a very hard, stern person who will bring forth the real crimes of the people who have oppressed them for them to really see it.”

There is a silver lining to the viral video, said Funnye, who is of the mind that more respectful language is absolutely effective in building bridges.

He believes that it will lead to more discussion, of which he is always a proponent. Visitors who come to his congregation will find a lot of diversity in the pews, he said.

“You will find Hispanic people. You will find Ashkenazi Jews, who have adopted African-American children. You will find Filipino Jews. You will find biracial Jews. Individuals with Jewish mothers and African-American fathers. You will find Jews from Nigeria, Ghana, the Caribbean and a broad spectrum,” he said. “Our congregation, I think, really resembles what the Jewish people around the world look like.”

Haynes said there’s a difference between Funnye’s congregation, which the latter says persistently builds bridges between Jews of African descent and the broader Jewish world, and extremist groups.

Haynes stopped short of describing the Black Hebrews in the video as members of a cult. But then he changed his mind.

“I think it’s important that people not get confused between those who really are seriously committed to their Judaism and those who maybe do fit the term ‘cult’ in the way that we tend to think of them,” he said.

In his first teaching job, at Yale University, Haynes noted a “meltdown in the public sphere” between segments of the black and Jewish communities.

But his own interactions with both Jews of African descent and white Jews were very positive.

He said that if he and his wife had had children, he would have likely converted to Judaism. Having kids, he said, has often been a catalyst for African-Americans who are married to Jews to convert to Judaism.

“I have such recognition within the community that in some strange ways there’s little pressure on me to convert,” he said. “It’s funny. I live the life of a stranger amongst Jews, in many ways.”

Meeting such a range of Jews of African descent, and studying those who self-identify as Hebrew and Israelite, has further convinced him that you can’t judge a group by its name.

“There are a million groups that call themselves the ‘Church of God,’” he said. “Just knowing that phrase will not help you understand anything about the people.”

By: Menachem Wecker