(RNS) — The Rev. Gerald L.K. Smith loved Jesus so much he built a seven-story statue on the top of an Ozark mountain to honor his savior.

Smith loved America, too, but despised many of his fellow Americans. Especially those who were Black, Jewish or immigrants.

An ordained Disciples of Christ pastor, master showman, skilled fundraiser, prolific writer and “minister of hate,” Smith spent decades warning white Christians that they were in danger of losing their country to devious forces conspiring against them.

To combat those forces, Smith founded a political party, ran for U.S. Senate and churned out tens of thousands of copies of The Cross and the Flag, a monthly magazine dedicated to the cause of Christian nationalism.

For Smith, that work was defined not by Jesus or the Constitution. His main concern was preserving Christian power and what he called “traditional Americanism.”

“The first principle for which we stand is: Preserve America as a Christian Nation being conscious of the fact that there is a highly organized campaign to substitute Jewish tradition for Christian tradition,” he wrote in “This Is Christian Nationalism,” which outlined the 10 pillars of his movement.

Among the other pillars of Christian nationalism: outlawing communism, destroying the “bureaucratic fascism” of income tax and the Supreme Court, and preserving racial segregation forever.

Smith aimed to take the latent prejudices and anxieties of American society and fan them into flames, wrote the late Glen Jeansonne, a longtime University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee history professor and Smith’s biographer. For Smith, the fear of communism was an excuse to embrace prejudice and pursue power.

“His life illustrates that the career of a person of remarkable talents can be tragic if it is guided by a lust of power and fueled by a bigotry that appeals to latent hatred,” wrote Jeansonne in his 1988 biography, subtitled “Minister of Hate.”

While Smith’s name is mostly forgotten, his ideas — and the strategies he used to promote them — still haunt America today.

“America has a long history, unfortunately, of this kind of Christian nationalism,” said Lerone Martin, associate professor of religion at Stanford University and director of its Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.

Debate over Christian nationalism, which sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry describe as “a cultural framework that blurs distinctions between Christian identity and American identity,” has been fueled by the rise of Donald Trump and the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

A recent survey by the Public Religion Research Institute and the Brookings Institution found that about 1 in 10 Americans favors an extreme form of Christian nationalism, while a 2021 Pew Research study found a similar number of “faith and flag” conservatives, whose faith in God and America are intertwined.

Yet Christian nationalism is defined by more than religion and patriotism, said Whitehead, co-author of “Taking America Back for God” and associate professor of sociology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. It’s also defined by hate.

For hard-core Christian nationalists, new and old, the enemies list has often included Jews, Black Americans, immigrants and progressives, often labeled as Marxists.

“One of the key parallels is an us-versus-them mentality where we have to circle the wagons because we are being attacked,” said Whitehead. “And the only way to survive is to fight back to take control and gain power.”

This tracks with PRRI’s poll, which found that Americans who believe that “Jewish people have too much power” are more likely to support Christian nationalist ideas than other Americans. Adherents of Christian nationalism, PRRI said, also believe that white Americans face as much discrimination as Black Americans and that America is being invaded by immigrants.

Proponents of Christian nationalism have long promoted their racist beliefs through Christian ideas, said Charles R. Gallagher, a Jesuit priest and professor of history at Boston College. This allows them to reach a larger audience that shares their beliefs but not necessarily their enemies.

“They are very shrewd in how they use the original principles of Christianity to suit their political or nationalistic goals,” said Gallagher, author of “Nazis of Copley Square: The Forgotten History of the Christian Front.”

Gallagher traces Christian nationalists back to the early 1900s, when conservative Christians witnessed firsthand Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution. Among them was William Dudley Pelley, a journalist and novelist, who’d gone to Russia as a volunteer for the YMCA and ended up covering the civil war for The Associated Press. He saw atrocities committed against Orthodox Christians by the Red Army.

“He experienced what he saw as a communist annihilation of Christian orthodoxy,” said Gallagher.

Also in Russia at the time was George Deatherage, a young engineer from Ohio, who’d gone to India to work for a steel company. As part of his job, he traveled to Russia and met with Russian exiles, where he also learned about the persecution of Christians.

Deatherage and Pelley returned to the United States with a fear of communism and what became an intense hatred of Jews, the latter fueled by a baseless conspiracy theory known as “Judeo-Bolshevism,” which blamed Jews for creating communism to threaten Christianity at the behest of a cabal of Jewish leaders bent on world domination.

Pelley, who also spent several years as a Hollywood screenwriter, would go on to found the Silver Shirts, a pro-Nazi fascist group. Deatherage resurrected the KKK-related Knights of the White Camellia and started the American Nationalist Confederation, a Christian group whose newsletter featured a Nazi hooked cross on a banner of red, white and blue.

Both Pelley and Deatherage promoted what Gallagher called “ecumenical anti-communism,” which sought to unite Protestants and Catholics in a grand, global conflict against Judeo-Bolshevism.

Smith and the Rev. Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest and star of the early days of radio, brought these ideas to a mass audience. Coughlin did it by way of his radio show, beamed across the nation by major networks and local stations; Smith by churning out his magazine, pamphlets, books and direct mail appeals in a never-ending stream.

“Few writers with so little literary skill have made such an indelible mark on so many people,” his biographer would write. “His words were like hoards of lemmings, plunging over a cliff into the sea. If he wrote enough, Smith thought, he could fill up the ocean.”

Even at a time when Catholics and Protestants often mistrusted each other, Coughlin and Smith found common ground in their hatred of communism, their antisemitism and their shared belief in both the cross and the flag.

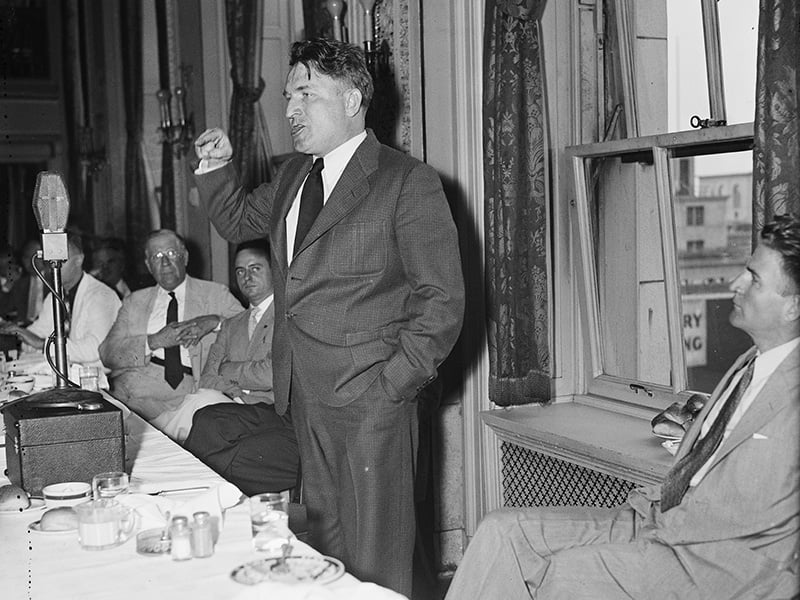

The two men eventually helped launched a third-party challenge to Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1936, promising to save the country from both the communists and Roosevelt’s big-money backers. At a convention organized by Coughlin’s National Union for Social Justice, Smith stood with a Bible in hand and gave a three-hour speech, promising to defend the Constitution, the Bible, Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny.

Like some modern Christian nationalists, Smith was both true believer and grifter, eager to promote his beliefs and build up his personal power, said Seth Cotlar, professor of history at Willamette University. Smith and other Christian nationalists also promoted “participatory anti-democracy,” said Cotlar, quoting a phrase coined by Princeton scholar Joseph Fronczak.

They were skilled, he said, at “getting people really fired up and mobilized in the name of fighting against democracy.”

Painting secular democracy as the enemy of Christianity, said Cotlar, Christian nationalists like Smith argued that the only patriotic way to save America from godless secularists was to vote for leaders who would ignore the rules of democracy. “It sounds really counterintuitive,” said Cotlar. “But it works if you perceive that the American democratic tradition is a tradition that hates you. It gives people a real sense of purpose and mission.”

Whitehead said political power has become an idol for modern Christian nationalists as well, one that can be used to justify anti-democratic action. Faith can then fuel that action.

“If a group legitimate their goals in the will of transcendent God, then what could stand in their way? The answer is nothing, not even democracy,” said Whitehead, whose new book, due out this fall, is titled “American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church.”

While Smith failed to gain political power and faded from memory, his ideas did not. Cotlar said he sees echoes of Smith in the current cultural debates over “wokeness” and the “deep state.”

Martin, author of “The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover,” said he also saw echoes of historic Christian nationalism in the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, something he believes the congressional investigation into the attack missed. “The Jan. 6 report … seems to want to lay almost all the blame on the president and not really take seriously the virus in the body politics that is Christian nationalism,” he said.

He said the committee investigating the attack dismissed the Proud Boys and other right-wing groups as fringe groups, not focusing on how much they represent ideas of Christian nationalism that remain in mainstream culture.

When Smith died in 1976, the Arkansas Gazette summed up his life this way, according to his biographer: “To have the power to touch men’s hearts with glory or bigotry and to choose the latter is a saddening thing.”

He had split much of his later years between California, where he ran a nonprofit called the Christian Nationalist Crusade, and Eureka Springs, Arkansas, where he built a series of Christian tourist attractions, including a Passion Play, a Holy Land Tour and a 65-foot-tall Jesus called “Christ of the Ozarks” on top of a mountain. The statue, made of concrete, was designed by the same sculptor who built a giant brontosaurus for Wall Drug, the famed South Dakota tourist attraction.

These monuments now seem quaint, of another age. But his legacy as a Christian nationalist seems more vibrant than ever.