(RNS) — For Pastor Seungeun Kim, accompanying North Korean defectors as they trek toward freedom through the jungle between Vietnam and Laos is, as he put it, “just going to work.”

“People are shocked about this rescue mission, but for me that’s part of my breakfast, lunch and dinner, morning, day and night,” Kim said in an interview conducted in Korean via translator. “It’s just regular life for me.”

Over the last 24 years, Kim estimates his organization, Caleb Mission, has helped rescue over 1,000 defectors from North Korea — in fact, he told RNS, he was in the jungle assisting defectors just days ago. But for many viewers of the new documentary, “Beyond Utopia,” now streaming on platforms including Amazon Prime and Apple TV, the footage of Kim’s rescue missions is extraordinary.

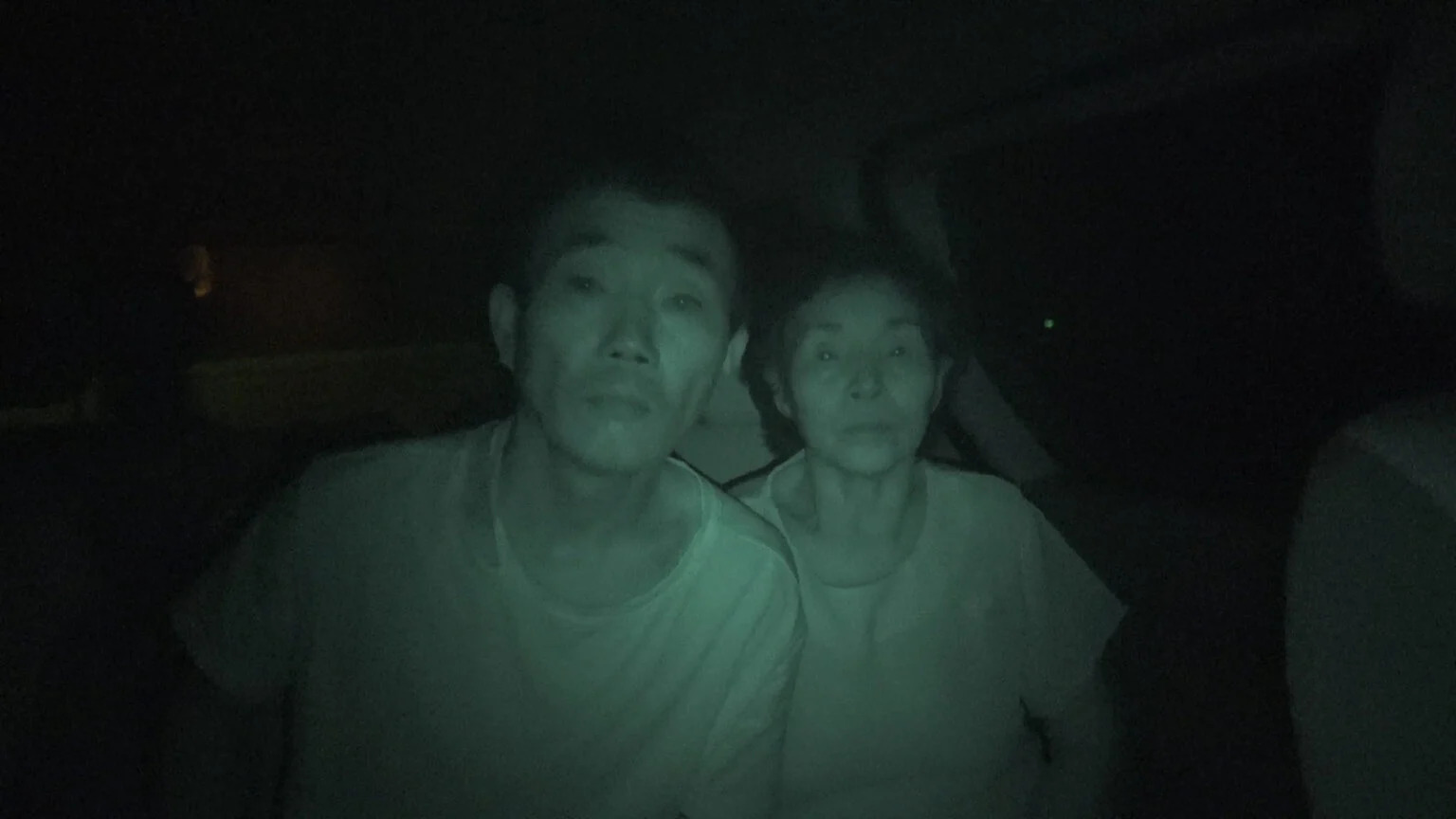

There’s the video of the Roh family huddled in a shack on China’s Changbai Mountain, begging Kim to provide resources for their escape. There’s the footage of the family scrambling through the jungle on foot, at night, led by brokers demanding more money. There’s the interview with the family in a safehouse, still recovering from years of North Korean propaganda, praising Kim Jong Un even while fleeing his government.

For director Madeleine Gavin — whose last project, “City of Joy,” documented women leaders in the Democratic Republic of the Congo — acknowledging the people of North Korea and hearing their stories is long overdue.

“I had to do it in a way that is up close and personal that really forces us to acknowledge people who we’ve ignored for such a long time,” Gavin told RNS.

During a trip to South Korea in 2019 to scope out ideas for a film on North Korea, Gavin met Kim, who told RNS he eventually agreed to the documentary “in order to help the people who are suffering from human rights abuses.”

That group includes the Roh family, who, around the time filming started in 2019, were informed they would be banished to an unlivable territory in North Korea for having relatives who had recently defected. The family of five fled across a river into China, where, through a series of chance encounters, they learned of Kim. The pastor mobilized his underground network and met the family in Vietnam, along with Gavin and a small film crew that captured the group’s escape through Vietnam, Laos and to the border of Thailand.

“I think, for all of us, we felt that what we were doing was so important and potentially meaningful in terms of getting the voices of North Koreans finally out to the world, that there was no turning back,” said Gavin. “As scared as everybody was at certain points, we felt we had to plow through and push through the fear because we really felt this was a necessary film.”

Gavin added that Kim’s commitment to God motivates him to not just oversee the missions, but to join defectors along the way wherever possible.

“He’s got many pieces of metal in his neck. He’s fallen off a cliff in Laos. You wouldn’t know it, but he’s always in pain. And yet he treks through the jungles. He goes on the boat across the Mekong when a group makes it that far. He has been shot at, in the past, on that boat.”

Kim is never shown proselytizing or forcing his faith on anyone, though he does pray openly and hopes the defectors experience God when prayers are answered. In a pivotal scene of the documentary, Kim prefaces a meal at a safe house in Laos with a prayer thanking Jesus for safety. At the end, he invites the Roh family to say “Amen.”

“That was the first time they heard the words, ‘In Jesus Name,’ because they were fresh from defecting,” said Kim. “That was the first prayer we did together, before the meal, even though they’d never heard about Jesus … Even though it was a simple, humble meal, to me that was the best meal, a meal from heaven. It made me forget all the hard time we went through.”

Though Gavin doesn’t consider herself religious, she described moments of feeling aligned with what she calls “the force,” a spiritual entity that’s “similar to what for some people would be God,” she told RNS. While filming this documentary, Gavin experienced a “heightened awareness” of “whatever this thing is.”

In a way, Gavin also created the documentary on faith. As recent defectors, the Rohs didn’t immediately understand what a documentary was, and Gavin felt she couldn’t ask them for consent to be in the film until they had time to “really get their heads around what’s happened,” she told RNS. The film’s other subject, Soyeon Lee, didn’t know at the start of filming what would happen to her teenage son, who was attempting to flee North Korea. Gavin and her team decided to wait as long as possible to get consent to use the footage.

Lee’s decision to be in the film was fraught. Between 2019 and 2023, Gavin’s team captured Lee’s optimism at the hope of being reunited with her son after over a decade, her fear after losing contact with him, her despair at learning he’d been caught and returned to North Korea, her desperation to organize another escape attempt and, finally, her unspeakable sorrow at learning he’d been sent to a political prison.

“I needed a lot of courage to even say yes,” Lee told RNS in an interview conducted in Korean with the assistance of a translator. “When I thought through it, my son is in a political prison in North Korea, the worst place in the world to be in. There’s nowhere he can go worse than where he is currently in. What can I do to help my son? I thought, if I say yes to this film, his story will go around the world. That way I can get international support and find any way to help my son.”

When she saw the film for the first time at the Sundance Film Festival this year, where “Beyond Utopia” won the Audience Award for U.S. Documentary, Lee wasn’t moved by the images of life in North Korea or the footage of the escape — as a defector herself, none of that was surprising.

As the film becomes available to view on streaming platforms, Kim hopes it might inspire viewers to support Caleb Mission’s goal of aiding as many defectors as possible. Recently, he told RNS, China increased the penalty for being caught helping a North Korean defector, and since COVID, the cost brokers charge to transport defectors has skyrocketed to $20,000 a person. In October, Human Rights Watch reported, Chinese authorities forcibly deported at least 500 refugees — mostly women — back to North Korea, where they are at risk of imprisonment, torture and execution. Kim said he currently knows of 200 people waiting in China for Caleb Mission to rescue them.

Gavin hopes the film humanizes the plight of the 26 million North Koreans cut off from the rest of the world.

“Every news organization, every person in every country, when we talk about North Korea, every single time we have to talk about the people. We can’t just talk about the missiles or the parades,” said Gavin. “I believe, and this is a form of spirituality, too, that there will be a ripple effect. Change is possible.”