BY : Bob Smietana Religion News Service

(RNS) — Jim Davis and Michael Graham knew something was up in their hometown of Orlando, Florida.

But they couldn’t put their finger on it.

At the time, both were pastors at Orlando Grace Church, an evangelical congregation, and saw a study showing their community had the same percentage of evangelicals as less traditionally Christian cities like New York and Seattle. Their city also ranked low on a list of “Bible-minded cities” — with a profile more akin to cities with secular reputations than Bible Belt communities like Nashville, Tennessee, or Birmingham, Alabama.

Which didn’t make any sense to them.

Orlando was home to the headquarters of Cru, a major campus ministry, along with Wycliffe Bible Translators and other major Christian nonprofits, as well as booming and influential megachurches like First Baptist and Northland Church.

And Orlando felt different from New York or Seattle.

“Then it hit us — it’s because our people used to go to church,” said Davis.

He and Graham knew of a number of people who had stopped going to church, and the two pastors started wondering how common that was. They began looking for data, and while there were studies of the so-called nones — those who do not identify with any faith group — there were few about churchgoing habits.

Eventually, they decided to do one of their own.

With the help of friends, they raised about $100,000 and enlisted the help of two political scientists who survey religious trends in the U.S. — Ryan Burge at Eastern Illinois University and Paul Djupe of Denison University — to create what they think is the largest ever study of folks who stopped going to church.

That study, combined with other data about America’s changing religious landscape, led them to a sobering conclusion.

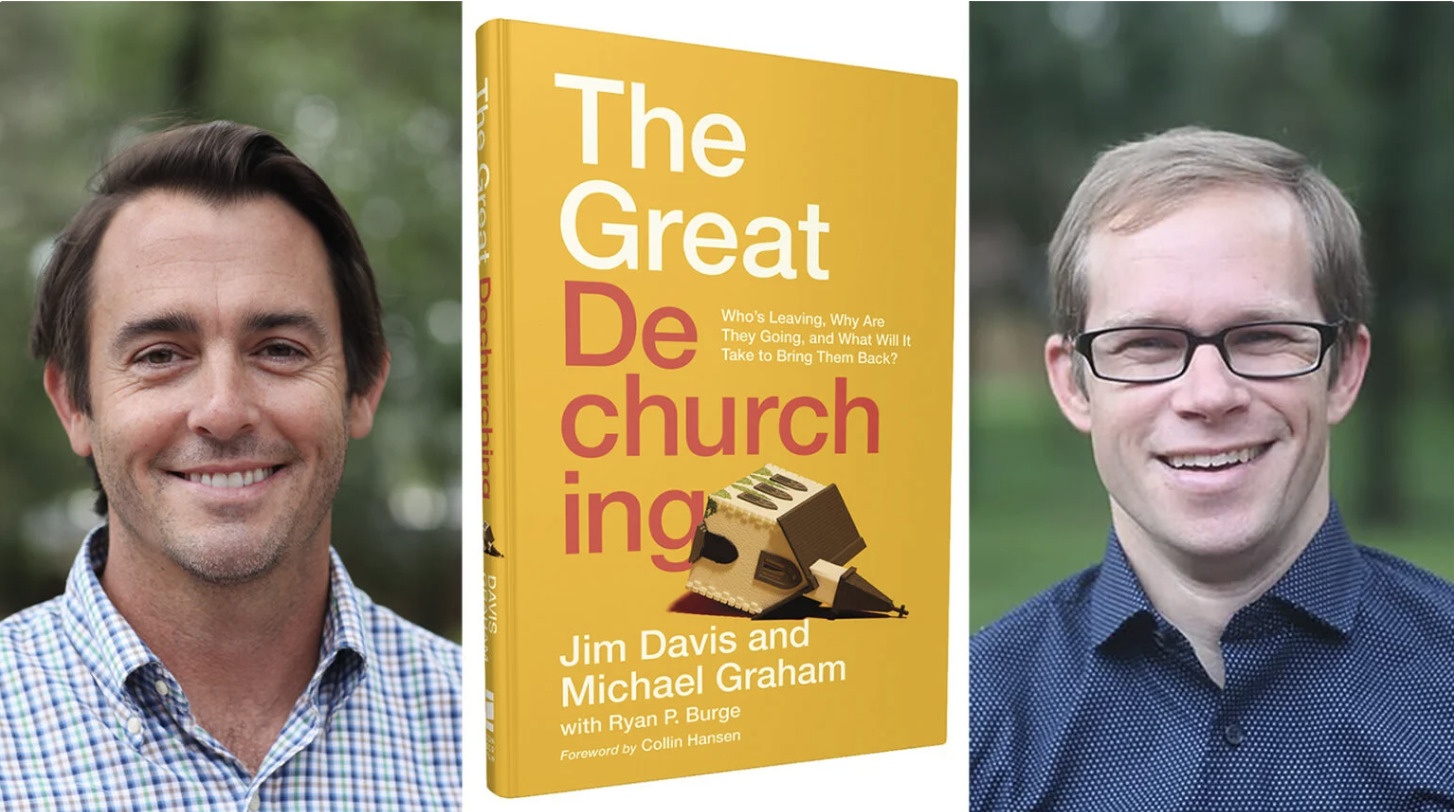

“More people have left the church in the last twenty-five years than all the new people who became Christians from the First Great Awakening, Second Great Awakening, and Billy Graham crusades combined,” Davis and Graham write in their new book, “The Great Dechurching: Who’s Leaving, Why Are They Going, and What Will It Take to Bring Them Back?”

The book and the study that prompted it were driven by both curiosity and stubbornness.

“If we’ve got a question that we need an answer to, we’re not going to stop until we get it,” said Graham, who is now program director for the Keller Center, which helps churches adapt to the changing religious landscape.

Davis and Graham said they wanted the study to be informative and rigorous, which is why they decided to work with academic researchers. The study included a survey of 1,043 Americans to determine the scope of dechurching — which was defined as having attended service at least once a month in the past and now attending less than once a year. That initial survey found that about 15% of Americans are dechurched.

A second phase included a survey with detailed questions for 4,099 dechurched Americans. Their answers were sorted in clusters using machine learning, said Burge — creating groups of people who had statistically similar answers to questions.

“It’s a wonderful way to look at religion without any sort of bias or prejudice,” said Burge. “It just lets the data speak for itself.”

The book appears to have struck a nerve with both church leaders and the broader public. Data from the book was featured in a series of New York Times columns about the changing religious landscape and what it might mean for American culture.

Burge said the book’s surveys build on previous studies of the nones as well as studies showing the decline of congregational life in the United States. The 2020 Faith Communities Today study, for example, found the median congregation in the United States stood at 65 people, down from 137 two decades ago.

A recent look at the impact of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic found that the median congregation in 2023 is now 60 people. Meanwhile, the Pew Research Center projects that nones could make up as much as half the population by 2070.

“For a long time, the church declined and no one really cared,” said Burge. “And now people are seeing the decline and saying, ‘Wow, this is really becoming a problem now.’ We have reached an inflection point where people are talking about religion in a more thoughtful, nuanced, statistically driven way.”

The dechurching study eventually yielded profiles of different kinds of dechurched Americans: ”cultural Christians,” who attended church in the past but had little knowledge about the Christian faith; “mainstream evangelicals,” a group of mostly younger dropouts; “exvangelicals,” an older group who had often been harmed by churches and other Christian institutions; “dechurched BIPOC Americans,” who were overwhelmingly Black and male; and “dechurched mainline Protestants and Catholics,” who had much in common despite their theological differences.

The researchers also sorted dechurched Americans into two major categories: the “casually dechurched,” who lost the habit of attending services because they moved or had scheduling conflicts; and “church casualties,” who stopped attending because of conflict or because they’d experienced harm.

Each of the five profiles had a wide range of reasons for leaving their churches and why they might be open to returning. For so-called cultural Christians, they left in part because their friends weren’t there (18%) and because attending was not convenient (18%) but also because of gender identity (16%) or church scandal (16%).

Mainstream evangelicals dropped out because they moved (22%) or services were inconvenient (16%) but also because they did not feel much love in church(12%). Exvangelicals in this study left because they did not fit in (23%), because they did not feel much love in the congregation (18%), because of negative experiences with evangelicals (15%) and they no longer believed (14%). Many BIPOC dechurched Americans left in their early 20s, often because they did not fit in (19%) or had bad experiences (11%). Mainline Protestants left because they moved (25%) or because they had other priorities (15%) or did not fit in (14%), while Catholics who are dechurched said they did so because they had other priorities (16%) or had different politics than others in their parish (15%) or the clergy (15%).

Davis said that people leaving churches is often seen as a catastrophe caused by church misconduct or hurt. That plays a role, he said, but the reasons people leave are more complicated and sometimes more mundane.

Dechurched also differ in why they might return. Mainstream evangelicals were looking for friendship, while mainline and Catholic dechurched Americans were more interested in spiritual practices and outreach programs.

Many dechurched Americans might return to churches if they found a stable and healthy congregation, said Davis and Graham. But those congregations aren’t always easy to find, given the level of polarization affecting churches and other institutions.

Among other findings, Americans who have higher levels of education or are more successful in life are less likely to drop out. That concerned Davis, who worries that churches only work for people on the so-called success path in life.

“Institutions in America tend to work for people who are on a traditional American path,” he said. “And unfortunately, the church has become one of those American institutions.”

Despite the sobering statistics, Davis and Graham remain hopeful about the future and end their book with a set of exhortations for church leaders.

Part of their advice: Be patient. The Great Dechurching didn’t happen overnight and won’t be reversed quickly. Congregations will need what the authors call “relationship wisdom” and a “quiet, calm and curious demeanor” where leaders are quick to listen and slow to speak.

“The path forward,” they write, “is not easy but it is simple.”

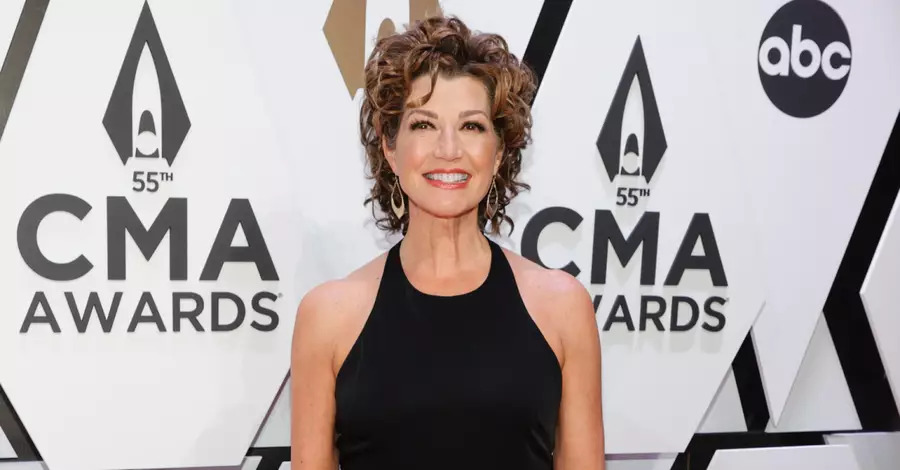

Courtesy images