BY : Heather Tomlinson Christian Today

The carol has remained a central part of our seasonal tradition for people of Christian faith and none. It is one of the few remnants of explicitly religious heritage that England has, and has even survived atheist attempts to sabotage it by rewriting the words to be more acceptable to secular ears.

The Yuletide carol has a tumultuous history, surviving many ups and downs over the centuries to bring us cheer in the cold winter months.

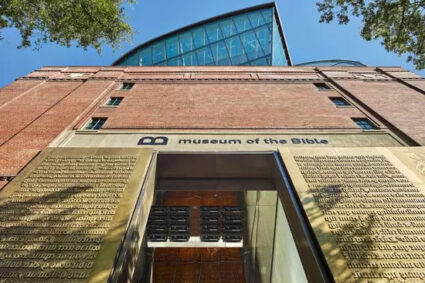

According to the Museum of the Bible, the first Christmas carol was introduced around AD 129, when the Bishop of Rome, Telesphorus, decided that churches must sing the ‘Angel’s Hymn’ at Christmas. This was based on the beautiful words of the angels celebrating the birth of Christ, recorded in Luke 2:14: “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favour rests” (NIV).

Church music developed through the following centuries, with the Mass punctuated by specified Latin chants, which were more elaborate during special seasons in the church year, especially Christmas and Easter.

The early carols were formal hymns in Latin, but we hear their echoes through the centuries as many were translated into local languages, such as Come, Thou Redeemer of the Earth and Of the Father’s Heart Begotten.

What we consider a ‘carol’ today is more akin to the church music equivalent of ‘pop’ music: the setting of Christian verse to folk melodies in the languages of the people. Medieval monks such as Adam of St Victor and St Francis of Assisi promoted these songs in the vernacular. In English, the earliest such carols are credited to the priest John Audelay, who died around 1426 and recorded The Little Flower and other early songs in his Caroles of Cristemas.

The Puritans in England were not keen on Christmas celebrations, so the humble carol was banned, though singing continued in secret behind closed doors. Various other movements in the church have altered officially sanctioned music, either rejecting or accepting the carol.

But the charm of carols for ordinary people has resisted all attempts to suppress them. Here are some of our most ancient and historic Christmas carols and the stories behind them:

O Come, O Come, Emmanuel

This Advent favourite started as a Latin hymn, based on the monastic tradition of singing the “O Antiphons” in the seven days leading up to Christmas, a practice that dates back to the 8th century or earlier. These antiphons each refer to an attribute of Christ: O Wisdom, O Lord, O Root of Jesse, O Key of David, O Dawn of the East, O King of the Nations, and O Emmanuel. They were sung before and after Mary’s hymn of praise, the Magnificat, which monks and nuns chant daily.

The tune we know today hails from at least 15th-century France, although it may well have earlier roots, as it resembles Gregorian chant, the most ancient kind of Christian music.

The Coventry Carol

This carol was part of one of the Coventry ‘mystery plays’ based on the Nativity, although they were usually performed in summer. The haunting minor key tune suits the mournful subject of the lyrics, which recount the massacre of the innocents by King Herod. The carol says goodbye to the young children through the repeated “bye, bye, lullay” refrain.

Here We Come A-Wassailing

Wassailing is the old name for carolling, where choirs went house to house singing Christmas songs and receiving a gift in return. This cheerful song commemorates that practice. The tradition is memorialised in Thomas Hardy’s Victorian novel Under the Greenwood Tree, as is the ancient tradition of arguing over music in worship.

The carol’s lyrics remind listeners of their obligation to donate to the singers, though there is little celebration of the birth of Christ. It does, however, ask for God’s blessing on the house.

The Holly and the Ivy

Like many folk songs and hymns, there are records of variations in both words and music linking holly, ivy, and Christmas. The tune we know best today was sung by a Mrs Mary Clayton in Chipping Campden, according to Cecil Sharp in his 1911 book English Folk-Carols.

The association of holly and ivy with Christmas is often interpreted today via the secular tendency to link Christian traditions to paganism. However, the use of these plants at Christmas is more rooted in medieval times when early carols featuring holly and ivy were sung. Evergreen plants were used to decorate homes for the season before modern tinsel and baubles.

Different regions had their own traditions: in the East Riding, evergreens were brought in on Christmas Day and removed by Twelfth Night, with strict instructions to throw them away rather than burn them to avoid bad luck. In other areas, they remained until Good Friday.

According to Susan Drury in a 1987 research paper, holly, ivy, and mistletoe became popular at Christmas “not only because they are evergreen, but because, unlike most other plants, they bear fruit in winter.”

O Holy Night

The French original, Cantique de Noël, first featured at a Midnight Mass in 1847. It became instantly popular and was soon translated into other languages, though the English version changes the meaning slightly. Unfortunately, the French church banned it, sensitive to its revolutionary message, strident tone, and certain theological elements. However, its popularity ensured its survival.

It is said to have been sung across the battlefield during the famous Christmas truce in WWI and is often voted among the public’s favourite carols.

What Child Is This?

The writer of this carol, William Chatterton Dix, nearly died in 1865 and endured a period of deep depression. However, he was spiritually renewed through prayer and went on to write several inspirational hymns, such as Alleluia! Sing to Jesus and As with Gladness, Men of Old. One of his first works was this Christmas carol, set to the traditional tune Greensleeves.

Heather Tomlinson is a freelance Christian writer. Find more of her work at https://heathertomlinson.substack.com/ or via X (Twitter) @heathertomli.

Photo: Getty/iStock