BY : Martyn Whittock Christian Today

The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews reminds Christians that they are surrounded by a great “cloud of witnesses.” (NRSV) That “cloud” has continued to grow in size since then. In this monthly column we will be thinking about some of the people and events, over the past 2000 years, that have helped make up this “cloud.” People and events that have helped build the community of the Christian church as it exists today.

My church once printed a New Year Motto Card that committed the community to “Prepare the hearts of the people and the structures of the church for the next great move of God.” As a Bible-believing evangelical fellowship, we were not expecting any radical new revelation. Rather we knew – as members of a 2000-year-old faith – that while core beliefs stand firm over the centuries, emphasis, structures and strategies can change – and change radically at times. The key is recognising the “move of God” in our particular time. Which raises the subject of John the Baptist and his followers.

Today, John the Baptist (not to be confused with the Apostle John) is held in high regard in Christianity, in Islam (where he is known, in Arabic, as Yaḥyā ibn Zakarīyā), in the Bahá’í Faith, and in Mandaeism (historically based in Iraq). All these faiths regard John as a prophet, and he is honoured as a saint among many Christians.

However, among the Mandaeans, John is revered as their greatest prophet and teacher; and their beliefs can be found expressed in their holy books, including the Ginza Rba (Great Treasure) and the Draša d-Iahia (Book of John). This radical view of the Baptist may be derived from gnostic beliefs that emerged from the second century onwards.

John the Baptist: the forerunner

As part of the preparation for the account of the birth of Jesus, the Gospel of Luke, chapter 1, introduces us to John the Baptist. We are told that he was the son of a priest named Zechariah, and Elizabeth his wife. Both, we are told, were descendants of Aaron, the brother of Moses. In this way John is given impeccable Old Testament prophetic roots which set him in the context of the great story of God revealing himself to the Jewish people. The reference to Aaron takes us back to the Exodus of the Jewish people from slavery in Egypt. We are, no doubt, meant to read this as a reminder of the great action of God about to be revealed.

John’s status within the ancient prophetic tradition (embodying the spirit and power of the revered prophet Elijah) and his bridge to greater to come (to prepare people for the Lord) is clear in Luke. Jesus himself later explicitly identifies John as “Elijah who is to come” (Matthew 11:14 and also Matthew 17:11–13), although in the Gospel of John, the Baptist expressly denies being linked to Elijah (John 1:21), which is intriguing and may indicate that Jesus and John differed in their interpretation of the Baptist’s role.

The synoptic gospels, though, insist on his status as fulfilling the role of that Old Testament prophet in preparing the way for the Messiah. In both Matthew and Mark, John’s unusual clothing is described in a way that recalls how Elijah is described in 2 Kings 1:8. There is, it should be clearly noted here, no hint of reincarnation, which is quite alien to Judaism, as later to Christianity.

In addition to the specific referencing of Elijah, the role of a prophet fulfilling Old Testament promises is explicitly connected with John. Mark (probably the earliest gospel written) describes John as a fulfilment of a prophecy from the Book of Isaiah concerning a messenger sent ahead preparing the way of the Lord and being “the voice of one crying out in the wilderness” (Mark 1:3).

In fact, the prophecy, as expressed in Mark, is a combination of verses from Isaiah, Malachi and Exodus. Some manuscripts of this gospel recognise this by substituting the words “as it is written in the prophets”. Matthew includes the same (modified) quotation from Isaiah 40:3 – “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God” – laying more emphasis on the “voice of one crying out in the wilderness” (Matthew 3:3), whereas Isaiah puts a little more stress on the place in which the preparation will occur. However, the meaning is clearly the same. Matthew then moves the verses from Malachi and Exodus to later in his account, where they are quoted by Jesus.

The location of John’s activities in the wilderness of the Jordan valley places him within the austere tradition of the ancient prophet, in contrast to the settled lives of the majority of the Jewish community in their villages and towns.

According to Luke, John’s message was one of personal spiritual renewal, moral transformation and social justice. It was a transformation signalled by adult water baptism. In this way John is presented as the forerunner of the actual Messiah. The baptismal events at the Jordan also echo the ancient exodus from Egyptian slavery which involved crossing that very river into the Promised Land.

The later Jewish historian, Josephus, when recounting (in Antiquities of the Jews) the execution of John in the fortress of Macherus, in the Judean desert on the orders of Herod Antipas, indicates that the reason was the popularity of John and the danger that this might have given him a platform for rebellion. With a message to all Israel, proclaimed by himself and so circumventing the temple and its priestly hierarchy and sacrificial activities, John was a huge challenge to the Jewish establishment of his day. He was living on borrowed time.

The potential political radicalism of John’s message is not fully explored in the gospels – which focus more on his spiritual role and message – and has been completely removed from Josephus’ account, with its agenda of reducing ideas of political conflict between Judaism and Hellenistic and Roman culture. However, at the time, John’s message was both socially challenging and politically charged. His denunciation of Herod’s marriage undoubtedly presented Herod with the very real danger that (what he would consider to be) radicalized Jewish subjects might combine with his Arab subjects in opposition to his rule. He acted to ensure that no such potential alliance could occur. The uncompromising moral stance of the Baptist led to his arrest and eventual execution.

Jesus and the Baptist

Exactly what the relationship was between Jesus and John, in the context of the time, has led to speculation. This has been fuelled by the fact that John’s ministry preceded that of Jesus and Jesus accepted baptism (which for everyone else was a sign of repentance) at the hands of John. Yet the gospel writers insist that Jesus (not John) is the Messiah and the Son of God. And later believers asserted Jesus’ sinlessness – a core Christian belief – which makes that key point of his baptism more complex and requiring explanation.

It is perhaps significant that in John’s Gospel there is no mention of the Baptist having an Elijah-anointing and there is no mention of Jesus’ actual baptism by John. The Baptist becomes more of a “voice” than a personality and, consequently, any questions concerning the meaning of Jesus’ baptism are avoided. This may well have been a product of the emphasis of this gospel on the exalted nature of Jesus the Christ, in combination with a wish to defuse problems (potential or actual) caused by continuing adherents of the Baptist who were still operating at the end of the first century. More on this last point shortly.

For the first generation of Christians, as they compiled the gospels in the second half of the first century (as for modern Christians), John the Baptist is the dramatic forerunner to the ministry of Jesus. He is the austere, uncompromising prophet who declares the coming of God’s kingdom and the imminent arrival of the Messiah. And then the Baptist rapidly fades from view.

The afterlife of the ‘John the Baptist Movement’

However, it is possible that we now underestimate the original dynamism and then the later potential rivalry between emerging Christianity and what we might call the ‘John the Baptist Movement.’

The gospels reveal that, even after John was imprisoned, his followers constituted a recognizable sect in contemporary Judaism, within the context of Galilee. And they seem to have been ascetic and puritanical. When criticising the (apparent) relaxed behaviour of Jesus’ disciples, when it came to socializing with those considered outcast “sinners,” a complaint was addressed to Jesus by the Pharisees and the teachers of the law that “John’s disciples, like the disciples of the Pharisees, frequently fast and pray, but your disciples eat and drink” (Luke 5:33). This gives an intriguing insight into the social, as well as theological, dynamic of Jesus and his followers. But it is important to also note it as an insight into the kind of community associated with John. This was a community that did not dissolve at the arrest and execution of the Baptist.

There is evidence that a complicated relationship between the two groups ran on into the middle of the first century and even beyond that. The New Testament Books of Acts refers to disciples of John active long after his death. At Ephesus, the Alexandrian Apollos, “had been instructed in the Way of the Lord; and he spoke with burning enthusiasm and taught accurately the things concerning Jesus, though he knew only the baptism of John” (Acts 18:25). Also at Ephesus, Paul met “some disciples” who had not heard about the Holy Spirit but had earlier been baptised “Into John’s baptism” (Acts 19:1–7). There were probably many others like them, whose activities have not been recorded and who varied in how they viewed the relationship between John and Jesus. The ‘John the Baptist Movement’ clearly had an afterlife and it had spread from its Judean and Galilean heartlands, just as Christianity had.

As late as the third century, documents known today as the Pseudo-Clementine Recognitions and Pseudo-Clementine Homilies record garbled traditions suggesting the continuation of a sect of “daily baptizers,” active long after the death of John the Baptist. We know little more about such people or their beliefs, but it looks as if a radical group continued to reference John as its founder. And it preached some kind of baptism-based ideology long after John had been executed. It may even have been seen as a potential rival to the Christian community until the end of the first century and even later. This seems reflected in some gnostic communities and in the community of the Mandaeans, with their exalted beliefs about him and their Draša d-Iahia (Book of John).

This tension may explain the explicit emphasis in the Gospel of John that, in the words of John the Baptist, “He [Jesus] must increase, but I [John the Baptist] must decrease” (John 3:30). Recorded in a gospel, completed perhaps as late as the 90s and probably conscious of continued competition between the two groups of followers, it was determined to set out theological priorities clearly. The message was transparent: John was the honoured but passing prophet; Jesus is the Messiah, the saviour, the revelation of the eternal nature of God. Interestingly there is, in this gospel, no hint of John’s doubts that we hear of elsewhere, when he asks from prison: “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” (Luke 7:19 and Matthew 11:3).

The Gospel of John also specifically refers to disciples of the Baptist leaving him (John 1:35–37) to follow Jesus, after John has declared that Jesus is “the Lamb of God.” However, the ‘John the Baptist Movement’ clearly did not just go away. For some of those who had invested in the ‘move of God’ that he embodied, it may have been quite challenging to accept that a greater ‘movement’ had occurred.

No such stark dilemma faces orthodox Christianity, committed as it is to the belief in the full and final revelation of God embodied in Jesus. But in other ways the challenge may be worth reflecting on. There can be a danger of clinging to the last ‘move’ when a new ‘move’ is occurring. It may be helpful to occasionally reflect on that, when reviewing one’s own churchmanship, emphasis and theology.

Martyn Whittock is a historian and a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England. The author, or co-author, of fifty-six books, his work covers a wide range of historical and theological themes. In addition, as a commentator and columnist, he has written for several print and online news platforms and been interviewed on TV and radio news and discussion programmes exploring the interaction of faith and politics.

His recent books include: Daughters of Eve (2021), The End Times, Again? (2021), The Story of the Cross (2021), Apocalyptic Politics (2022), and American Vikings: How the Norse Sailed into the Lands and Imaginations of America (2023). The afterlife of the ‘John the Baptist Movement’ is one of many areas explored in his co-written book, Jesus the Unauthorized Biography (2021).

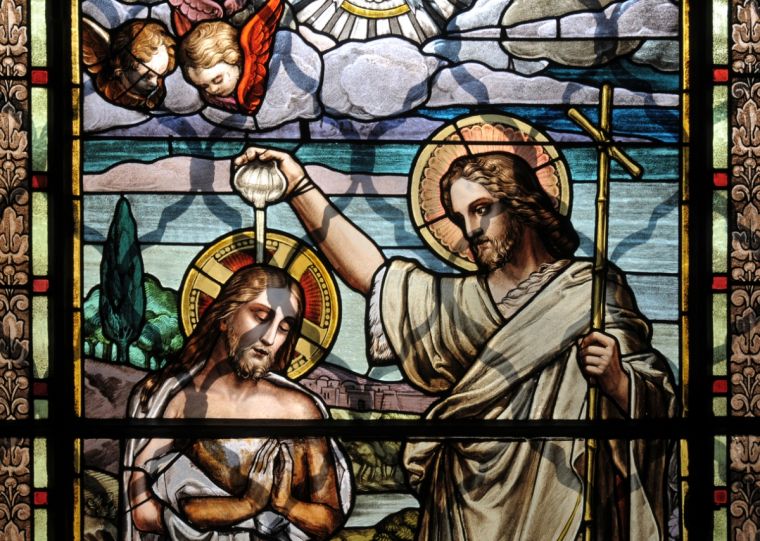

Photo: Getty/iStock