BY : Jack Jenkins Religion News Service

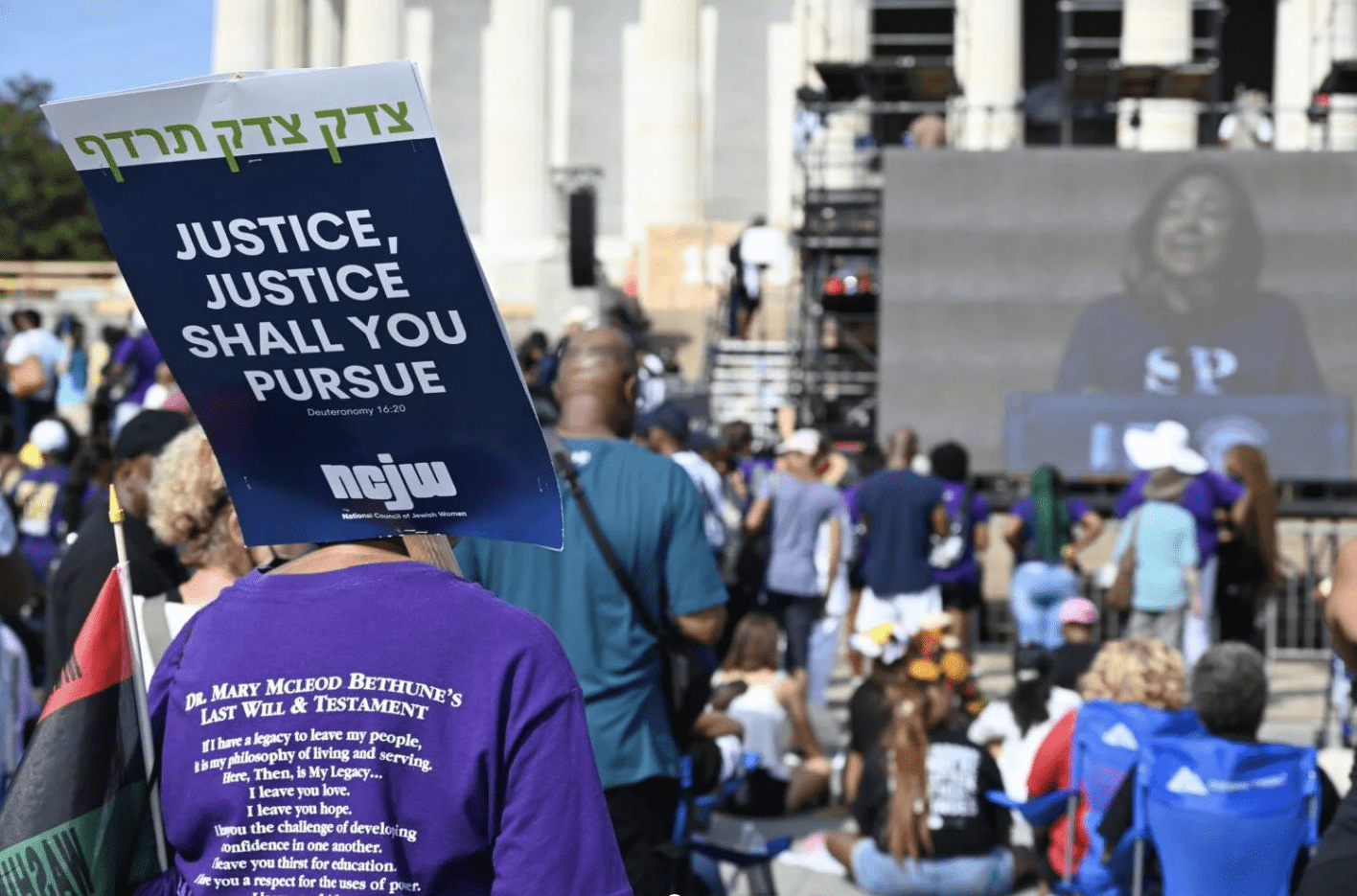

“Sixty years ago, Martin Luther King talked about a dream,” said the Rev. Al Sharpton, referring to King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. “Sixty years later, we’re the dreamers — the problem is we’re facing the schemers.”A demonstrator watches a speaker at the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.,

WASHINGTON (RNS) — Thousands of people assembled near the Lincoln Memorial on Saturday (Aug 26), to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington, paying tribute to the historic civil rights gathering led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., while voicing new frustrations with political extremism that threatens racial progress.

In his address to a sprawling crowd, the Rev. Al Sharpton, founder of the National Action Network, framed the country’s current political contest as a battle between “dreamers” and “schemers.”

“Sixty years ago, Martin Luther King talked about a dream,” said Sharpton, referring to King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered from the same spot in 1963, in which the slain civil rights leader envisioned a future of racial harmony. “Sixty years later, we’re the dreamers — the problem is we’re facing the schemers.”

“The dreamers are in Washington, D.C.,” Sharpton said. “The schemers are being booked in Atlanta, Georgia in the Fulton County Jail.”

As if to underscore the nation’s continuing need to for racial justice, a white gunman fatally shot three people at a Dollar General store in Jacksonville, Florida, Saturday, in what the sheriff there described as a “racially motivated” killing.

As in 1963, a dizzying array of activists, faith leaders, musicians, actors, labor advocates and lawmakers delivered their own impassioned speeches, standing for a broad coalition addressing racial injustice. It is credited with helping to spur passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Like Sharpton, the Rev. Jamal Bryant, pastor of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church in Lithonia, Georgia, made reference to Trump’s most recent indictment broadening the term to criticize churches that don’t do enough to help those in need.

He called for an “indictment on churches that are silent — they speak in tongues, but don’t speak truth to power” and “an indictment of those who have multi million dollar buildings, but a close up to those who do not have a standard of living.”

Bryant’s frustration with DeSantis was echoed by the Rev. R. B. Holmes, Jr., pastor of Bethel Missionary Baptist Church in Tallahassee, Florida. Standing a few feet from the steps of the memorial, Holmes pointed to Florida’s widely criticized efforts to alter the way Black history is taught in the state, including instructing students that African Americans “developed skills” while enslaved “which, in some instances could be applied for their personal benefit.”

“I’m here because we have a governor in my state of Florida trying to take us back to the to the dark past,” Holmes told Religion News Service. “I’m here because God has called us to stand up against the Sanders and Goliath. We cannot allow this government this system, this far-right extreme group, to deny our history, water down Black history, did not Black history, uplift nationalism, and diminish black history.”

Rabbi Heather Miller, a Black woman and founder of The Multitudes, recalled the different faiths represented at the 1963 march and offered her presence as evidence of solidarity across different identities and faith traditions.

“When we talk about Black and Jewish unity, we call upon images of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marching together 60 years ago on days like these,” she told the crowd. “While it is certainly true that there are times when there is disunity between the two identities of mine … there is an energy in the air right now that seems to be radiating off of everything. And me, getting to stand here as a Black rabbi, it does not get any more harmonious than this.”

Standing near the front of the crowd with a group affiliated with the National Council for Jewish Women, Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg said the organization has long tied causes such as resisting antisemitism to similar efforts to resist racism perpetrated against Black people. She noted that NCJW sponsored an anti-lynching bill in the early 1900s, and expressed hope others would take similar steps to address modern fights.

“We’re here because this is a Jewish issue — Black Jews’ rights are at stake,” she said. “We’re here because this it is our obligation as Jews to make sure that every single human being on this planet has possibility to thrive and to live up to their fullest potential. And right now, our country is deeply unjust.”

Rep. Debbie Wassermann Schultz of Florida and Rep. Nikema Williams of Georgia, co-chairs of the Congressional Caucus on Black-Jewish Relations, made a similar argument during a joint address later in the day.

“The Black and Jewish communities are united and strong,” Schultz said.

Williams summoned the image of the late Rep. John Lewis, a civil rights icon and a co-founder of the caucus who spoke at the first march.

“To this day, the interconnectedness remains strong, y’all,” Williams said. “As we face rising hate speech and antisemitism, attacks on our basic freedom and attempts to erase our history, we know that when we fight together victory is ours.”

Members of King’s family spoke, as did figures such as House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries of New York; Kelley Robinson, president of the Human Rights Campaign; David Hogg, a mass shooting survivor and gun control advocate who co-founded the group March for Our Lives; and Sacha Baron Cohen, a British comedian and actor, among many others.

The blitz of speeches and causes did little to faze a woman who stood nearby under a shady tree, who nodded thoughtfully throughout the day as she listened to people speak. Wearing the T-shirt of her New York church and offering only her first name, Mary, she told RNS that while she hadn’t made it to the March on Washington in 1963, she managed to show up for the original Poor People’s Campaign a few years later in 1968 — an effort initiated by King just before he was assassinated that same year.

The experience, she said, helped catapult her into a lifetime of grassroots activism.

“I’m concerned about democracy in this country — very concerned,” she said. “And I’m concerned about this upcoming election. We’re at a pivotal point in this country.”

Even so, she grinned as she looked out at a group of young huddled people nearby, many of whom are around the same age she was when she attended at rally here decades before.

“In spite of how far we have to go, we have come so far,” she said.

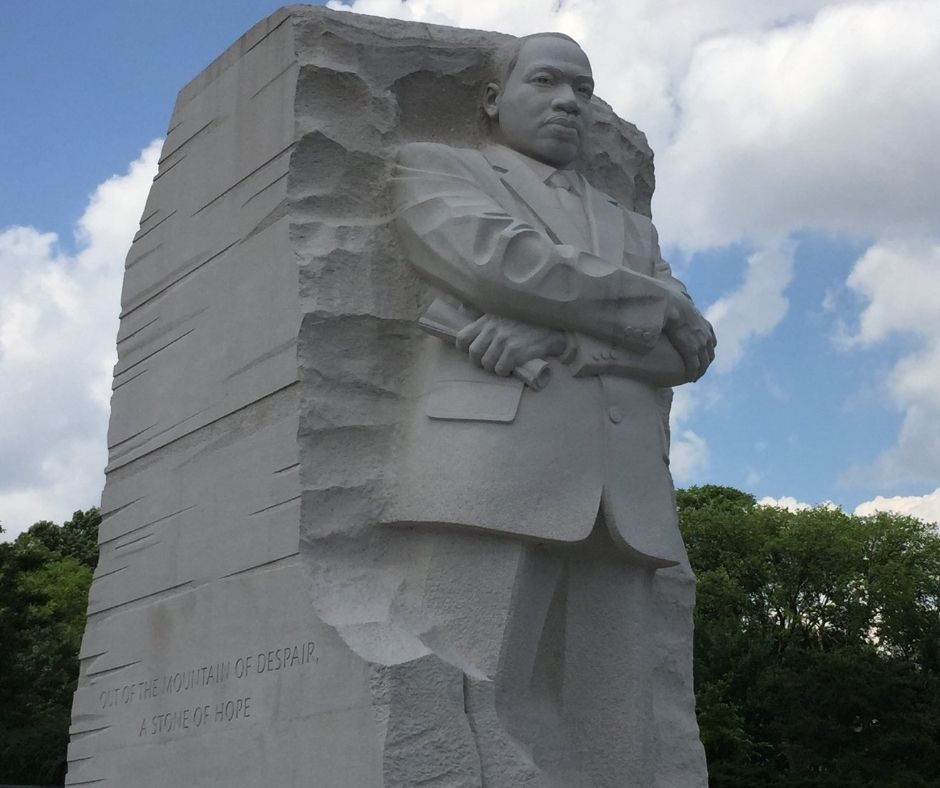

As the event concluded, the crowd then turned and marched to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial.

RNS photo by Jack Jenkins.