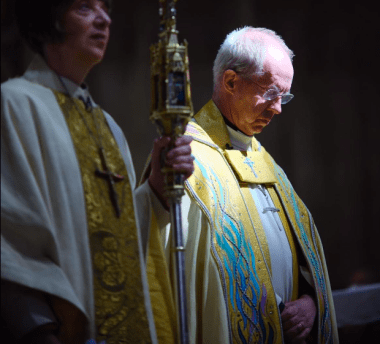

BY : Martin Davie Christian Today

On Tuesday 12 November the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, announced his intention of resigning in the wake of the independent review by Keith Makin into the abuse carried out in this country, Zimbabwe and South Africa by the late John Smyth.

The Archbishop’s statement declared:

“Having sought the gracious permission of His Majesty The King, I have decided to resign as Archbishop of Canterbury.

“The Makin Review has exposed the long-maintained conspiracy of silence about the heinous abuses of John Smyth.

“When I was informed in 2013 and told that police had been notified, I believed wrongly that an appropriate resolution would follow.

“It is very clear that I must take personal and institutional responsibility for the long and retraumatising period between 2013 and 2024.

“It is my duty to honour my Constitutional and church responsibilities, so exact timings will be decided once a review of necessary obligations has been completed, including those in England and in the Anglican Communion.”

It is important to note that the Archbishop of Canterbury is still in post. He has said that he will resign in due course at a date yet to be determined and it is not clear when that will be. Further information about the timing of his resignation has not yet been released.

What is clear, however, is that once his resignation has formally taken place via an instrument of resignation submitted to the King, the Archdiocese of Canterbury will be declared vacant by the King via an Order in Council, and a process to appoint the next Archbishop of Canterbury will take place. This process will have two parts to it.

The choice of candidates by the Crown Nominations Commission

The first part is a process to choose two agreed candidates to be recommended to King Charles for appointment as archbishop.

From the time of Henry VIII onwards it has been the law that bishops of the Church of England are appointed by the monarch. From 1821 onwards it has also been the convention that the monarch accepts the advice of the Prime Minister on this matter and since 1976 there has been a process in place involving the Crown Nominations Commission (CNC) by means of which the Church of England chooses candidates for diocesan bishoprics who are then submitted to the monarch by the Prime Minister for appointment. In the case of suffragan bishops, the diocesan bishops involved put forward the names of candidates to the Prime Minister to be submitted to the monarch.

As the Archbishop of Canterbury is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury the appointment of a new archbishop involves the work of the CNC and follows the rules for the work of the CNC laid down in the standing orders of the Church of England’s General Synod.

The composition of the CNC varies depending on whether it is an ordinary bishop or an archbishop who is being appointed. In the case of the appointment of a new Archbishop of Canterbury the composition of the Commission is as follows:

- A lay Chair appointed by the Prime Minister

- A bishop elected by the House of Bishops

- The Archbishop of York or, if they choose not to be a member of the CNC, a further bishop to be elected by the House of Bishops

- Three representatives of the Diocese of Canterbury elected by the dioceses’ Vacancy in See Committee

- Six members of the Commission (three clerical and three lay) elected by the General Synod to serve on the Commission for a five-year period

- Five representatives from other churches in the Anglican Communion – one each from Africa; the Americas; Middle East and Asia; Oceania and Europe. These representatives have to include at least two women and two men and at least three of them have to be of ‘Global Majority Heritage.’

- The Secretary General of the Anglican Communion, the Prime Minister’s Appointments Secretary and the Archbishops’ Secretary for Appointments are also members of the Commission, but they do not have a vote.

Prior to the first meeting of the CNC a consultation process will be held by the Church of England to determine the needs of the Diocese of Canterbury, the Church of England and the Anglican Communion with regard to the new archbishop. After this process has taken place, the CNC will then meet to agree its processes and review potential candidates.

Following an interview process, an agreed candidate will be chosen by the voting members of the CNC. This candidate will need to receive at least two thirds of the votes cast in a secret ballot. It has recently been suggested that the requirement for a two thirds majority should be changed, but unless and until this happens through a vote of the General Synod this requirement remains in place. In addition, the CNC must also agree on the name of a second candidate in case it becomes ‘impossible to appoint’ the agreed candidate.

In theory any member of one the churches of the Anglican Communion could be chosen as a candidate to be the next Archbishop of Canterbury (the previous archbishop, Rowan Williams, was, for example, a member of the Church in Wales). The person chosen could be either male or female and would not actually need to be ordained at the point they were chosen, although they would need to be ordained deacon and then priest prior to their appointment, at which point they would then be consecrated as a bishop.

In reality, however, the likelihood of someone who was not ordained being chosen is vanishingly small, and recent history strongly suggests that the chosen candidate will be someone who is already a diocesan bishop.

After the CNC has chosen the name of its two preferred candidates, the first name will be sent to the Prime Minister for submission to the King. Since 2007, the Prime Minister has accepted the CNC’s recommended candidate and tendered their name to the Monarch, but in theory the Prime Minister could refuse the first name and ask for the second name to be submitted instead. Should the Prime Minister or the King refuse both names this would be unprecedented and would cause a serious crisis in church-state relations. It is therefore unlikely to happen.

The formal process of appointment and enthronement

The second part of the process takes place once a name has been submitted to the King and agreed by him. This part of the process is based on the Appointment of Bishops Act which was passed in 1534 in the reign of Henry VIII.

This part of the process has five elements.

(1) The King sends to the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral the conge d’elire, which is the licence giving them permission to elect. The licence is accompanied by a Letter Missive from the King containing the name of the person chosen by the Crown and instructing the chapter to elect him or her. Theoretically the Dean and Chapter could refuse to elect the royal candidate. However, if they did so, the King could then proceed to appoint the person anyway by means of royal Letters Patent. In fact, the chapter invariably does elect the royal nominee.

(2) The King will then give royal assent to the election by the Dean and Chapter by means of Letters Patent. These will also command the Archbishop of York and other senior bishops to legally confirm the result of the election. When they have done this via a formal legal ceremony the person elected officially becomes the Archbishop of Canterbury and is able to exercise the spiritual functions of that office.

(3) In the unlikely event of the chosen candidate not already being a bishop, they would then be consecrated as a bishop by the Archbishop of York, other bishops assisting.

(4) Following the consecration, or the confirmation of election, if someone is already a bishop, the new Archbishop of Canterbury will then pay homage to the King and receive the temporalities of the archbishop’s office. The ‘temporalities’ are the property and revenues belonging to a bishop, which are administered by the Crown during an episcopal vacancy and are then restored to a new bishop. Traditionally these temporalities consisted in the episcopal residences and estates, but because these are now vested in the Church Commissioners as part of the historic assets of the Church of England, what they consist of today is the right to appoint incumbents to some of the benefices in the diocese, in this case the Diocese of Canterbury.

The archbishop will also become a member of the House of Lords (unless they are already a member) and a member of the Privy Council (unless they were previously Archbishop of York or Bishop of London in which case they will already be a member).

(5) Finally, the new archbishop will be enthroned in the chair of St Augustine in Canterbury Cathedral. This ceremony possesses no legal significance, but it marks the ceremonial and public entry of the new archbishop into his cathedral, diocese and province and into the role of senior bishop of the Anglican Communion.

The challenge facing the CNC and a possible way forward

Although the procedure for formally choosing and appointing a new Archbishop of Canterbury is thus clear, what is much less clear is how it will prove possible for the CNC to choose a candidate who is acceptable across the breadth of both the Church of England and the Anglican Communion.

The deep divisions within the Church of England and the Anglican Communion over the issue of human sexuality which have opened up since 2003 and which have become even more pronounced during the tenure of Archbishop Welby, mean that it will become very difficult, if not impossible, to find someone who the Church of England as a whole and the Anglican Communion as a whole will be able to agree upon. If a candidate takes a conservative view on human sexuality this will make them unacceptable to the liberals in the Church of England and the Anglican Communion and vice versa.

The question that therefore arises is whether it might not be sensible to hold off from appointing a new archbishop until there is the sort of reconfiguration of the Anglican Communion suggested by the Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches and the sort of reconfiguration of the Church of England suggested by the Church of England Evangelical Council and the Alliance.

This would solve the problem because a liberal Archbishop of Canterbury could be appointed who would be acceptable to liberals in the Church of England and across the Communion, but conservatives in the Church of England and the Anglican Communion would no longer come under his archepiscopal authority.

This is an idea that needs to be taken seriously to avoid the choice of a new archbishop mirroring or indeed exacerbating the division which already exists across the Anglican world.

Photo: Lambeth Palace