Another commenter, “CommonSense,” chimed in that the concern of the “Founding Fathers” was “to protect religion from the government, not to protect the government from religion.”

These are examples of what over the past couple of decades has become religious right boilerplate, promoted most notoriously by faux historian David Barton in an unending stream of books, videos and speeches. Now it’s being used to advance public policy.

Separation of church and state is “not a real doctrine,” declared Texas state Sen. Mayes Middleton as he successfully urged his colleagues to pass bills mandating display of the Ten Commandments in public schools, requiring school districts to set aside time for staff and students to pray and read religious texts and allowing administrators to hire chaplains.

Not a real doctrine?

Why yes, “separation of church and state” does not appear in the Constitution. But neither does “religious liberty” or “religious freedom,” yet you don’t find a lot of folks saying that these aren’t American things.

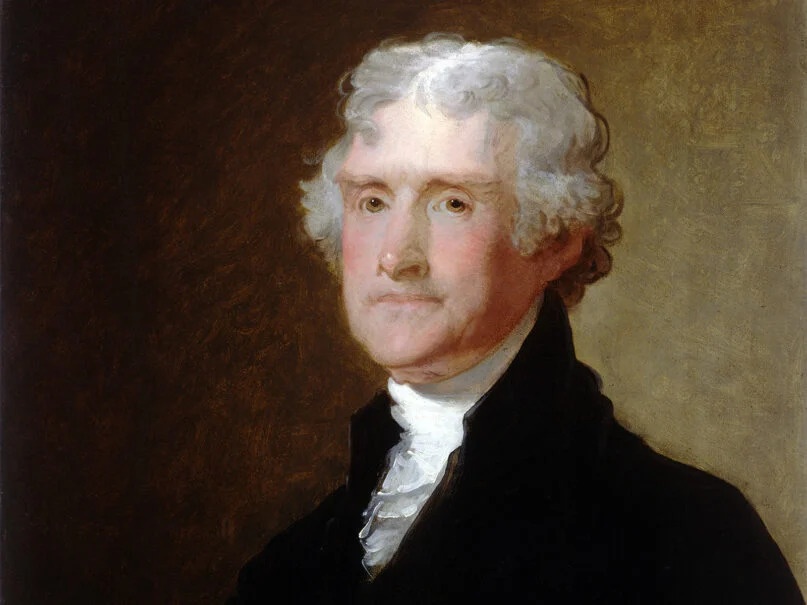

What’s important to know is that “separation of church and state” only exists as a concept because that’s how Thomas Jefferson characterized the religion clauses of the First Amendment in his famous letter to a group of Baptists in Connecticut. To wit: “‘I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

You may not like Jefferson’s metaphor, but as a concept, “separation of church and state” meant, for him, nothing more nor less than what the First Amendment has to say about religion. (That Jefferson may have borrowed the metaphor from 17th-century Baptist Roger Williams’ image of a “wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world” is another question.)

Jefferson’s separation aside, there was broad-based support at the constitutional convention (which Jefferson did not attend) for disengaging religion from the business of government. Before getting around to the Bill of Rights, the framers put the following language into Article Six: “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

Not that all convention delegates approved. Luther Martin, the shrewd if bibulous lawyer representing Maryland, reported to his state legislature that “a great majority of the convention” had voted, with little discussion, that there be no religious test for holding federal office — adding the testy caveat that there were some members, himself clearly among them, “so unfashionable as to think, that a belief of the existence of a Deity, and of a state of future rewards and punishments would be some security for the good conduct of our rulers, and that, in a Christian country, it would be at least decent to hold out some distinction between the professors of Christianity and downright infidelity or paganism.”

What the delegates wanted to make clear was that the federal government would have no part of the English Test Oath, which required members of Parliament to make a declaration against transubstantiation, invocation of saints and the sacrament of the Mass, thereby excluding Catholics. The government of the United States should give (as Washington wrote to the Jews of Newport in 1790) “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.”

Finally, let’s unpack the claim that the founders sought to protect religion from the government and not vice versa. The protection of religion mostly had to do with their belief that religion is corrupted when incorporated into government affairs — as per Roger Williams’ desire to keep “the wilderness of the world” from overrunning the church.

Or as founder James Madison put it in his Memorial and Remonstrance of 1785, employing religion in the service of civil policy is “an unhallowed perversion of the means of salvation.”

But Madison also understood that government needed to be protected from religion. In the same treatise, he denounced ecclesiastical establishments in no uncertain terms: “In some instances they have been seen to erect a spiritual tyranny on the ruins of the Civil authority; in many instances they have been seen upholding the thrones of political tyranny: in no instance have they been seen the guardians of the liberties of the people.”

So far as I know, Texas has not ordered the Memorial and Remonstrance removed from public school libraries. Yet.